When it comes to the history of hemophilia, there’s a lot to unpack. The public didn’t even have a name for the disease until 1928, but hemophilia had a big impact on world affairs even before then — an impact that would give way to its nickname, the “Royal Disease.” Its history doesn’t start there, though. Far from it: You could go back as far as ancient Egypt to find records of people experiencing irregular bleeds, a symptom of bleeding disorders such as hemophilia.

As for the origins of its royal nickname, you need to go back to the 19th century.

Why Hemophilia Is Called the Royal Disease

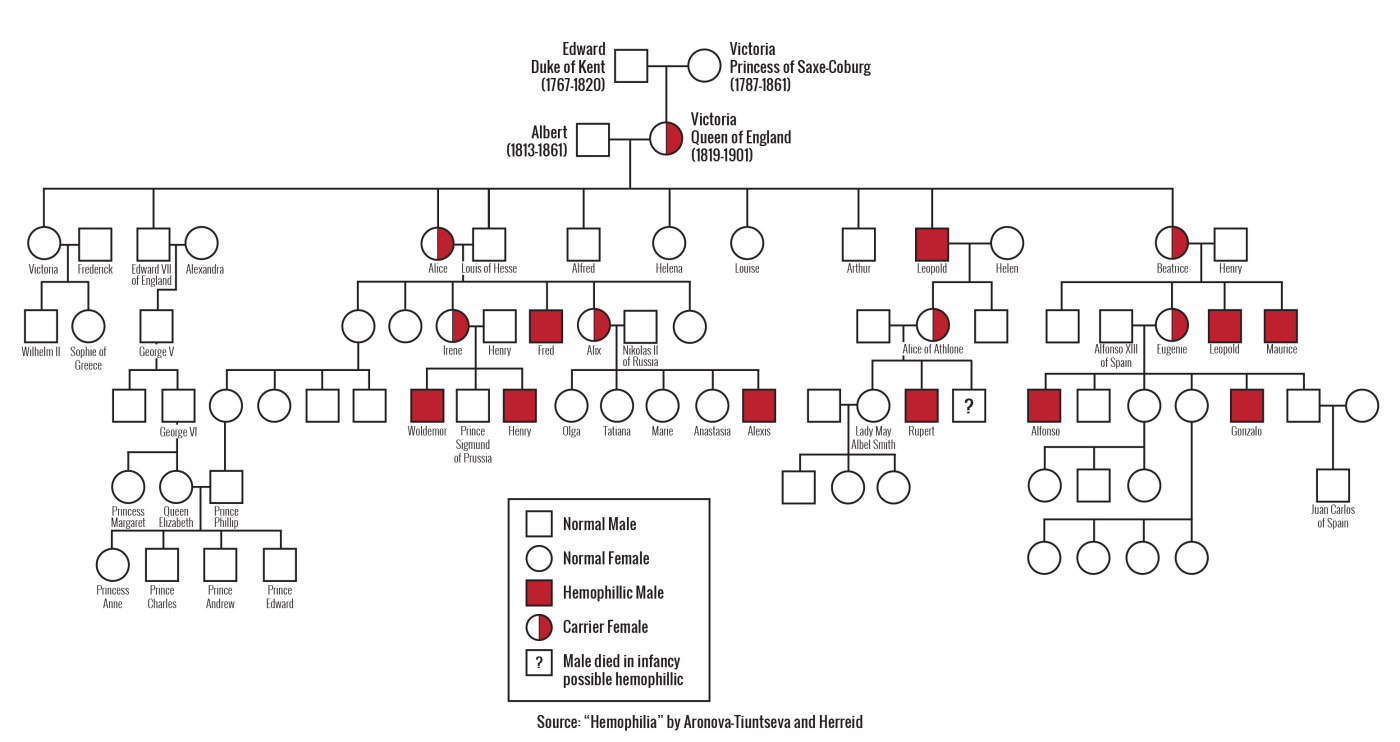

Hemophilia’s stately moniker comes from its prominent effect on European royalty in the 19th and 20th centuries, affecting English, German, Russian, and Spanish nobility. Queen Victoria of England was a carrier of the disease and passed it along to three of her nine children, one being her son Leopold. She also passed it to her daughters Alice and Beatrice, who then passed it along to their children who married into the royal families of Russia, Spain, and Germany. Historians believe the queen was the one to introduce hemophilia to her bloodline, receiving the bleeding disorder through a spontaneous gene mutation.

Queen Victoria didn’t exhibit symptoms, nor did the two daughters she passed hemophilia to. However, her son Leopold dealt with the effects of the disease his whole life. From a very young age, he appeared physically weak, bruised very easily, and was often in pain. He was under constant supervision, as any cuts or bleeds could have had dire consequences.

Treatment didn’t exist at the time, but prominent doctors tried to ease his suffering, including John Wickham Legg, who wrote the famous A Treatise on Haemophilia, which he published in 1872, five years after he stopped attending to Leopold. As a member of the British royal family, Leopold and his condition brought much more attention to hemophilia, which led to an increase in publications in the 1880s and more research toward a cure. Prince Leopold died at age 30 after a minor fall.

How Hemophilia Spread Across Royal Families

Alice’s Family

Queen Victoria’s daughter Alice passed hemophilia to the German and Russian royal families. She married Louis IV, the grand duke of Hesse and by Rhine, a territory in western Germany that existed until 1918. Alice then passed hemophilia on to at least three of her children, one being Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine, who later became Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia after marrying Tsar Nicholas II. Alexei, Feodorovna’s child (Alice’s grandson) and heir to the Russian throne, inherited hemophilia and showed symptoms at just months old. His bleeding disorder caused him constant pain, before he and his family were assassinated when he was just 13 years old.

Beatrice’s Family

Queen Victoria’s youngest child, Beatrice, passed hemophilia to the Spanish royal family. Beatrice married Prince Henry of Battenberg, then passed the bleeding disorder on to at least two of their four children. One inheritor of hemophilia was Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg, who later became Queen Victoria Eugenia of Spain through her marriage to King Alfonso XIII.

Eugenie then passed it on to her children, including Alfonso, Prince of Asturias, heir to the Spanish throne; he died at age 31, bleeding to death after a car accident. Eugenie also passed it on to her two daughters, Infantas Beatriz and Maria Cristina of Spain, but none of their descendants have been known to have hemophilia.

Is Hemophilia Still Royal?

There are no known living members of the European royal families or of past dynasties who have hemophilia. However, some point out that with the possibility of silent carriers in many of Victoria’s great-granddaughters, there remains a small chance that the disease could appear again.