One of the probably lesser known—and certainly most far-flung—of the 140-plus federally designated US hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs) will soon recognize a significant milestone. This fall the Guam Comprehensive Hemophilia Care Program (GCHCP) will celebrate 20 years of helping members of the small bleeding disorders community go from living their lives controlled by their bleeding disorder to controlling their bleeding disorder to live their lives.

To understand how far the Guamanian bleeding disorders community has come in the past two decades, it helps to understand a little about the island. Guam is small, both in size and population. Roughly 170,000 people currently live on the Western Pacific island, about 40 of whom are known to have a bleeding disorder. A United States territory since 1898 (residents born there are US citizens), Guam is geographically closer to mainland China than the mainland US.

Prior to the establishment of the GCHCP, Guamanians with bleeding disorders relied mainly on emergency room care. In the case of serious or life-threatening bleeds, patients boarded a plane and flew more than seven hours to Tripler Army Medical Center in Honolulu, under the auspices of the US military’s Pacific Island Health Care Project.

There was little knowledge within Guam’s medical community regarding the diagnosis and treatment of hemophilia, von Willebrand disease (VWD) and other rare bleeding disorders.

By the mid-1990s, however, social workers in the Medical Social Services (MSS) section of Guam’s Department of Public Health and Social Services (DPHSS) were increasingly aware that families affected by bleeding disorders needed more assistance. This movement for better care got a boost after a single phone call.

By the mid-1990s, however, social workers in the Medical Social Services (MSS) section of Guam’s Department of Public Health and Social Services (DPHSS) were increasingly aware that families affected by bleeding disorders needed more assistance. This movement for better care got a boost after a single phone call.

One day in 1995, Judith Baker, DrPH, MHSA, regional coordinator of the Western States/Region IX Hemophilia Treatment Center Network, received an urgent call at her Southern California office. The Region IX network covers California, Hawaii, Nevada and the six United States’ Pacific island jurisdictions. With the commercial internet in its infancy, and communication by phone and fax generally spotty, real-time information regarding the Pacific jurisdictions was limited. But on this day the caller on the other end of Baker’s phone was in Guam, 6,100 miles off the California coast.

Baker’s office had just conducted a survey throughout the US Pacific jurisdictions (Guam, American Samoa, Belau, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Marshall Islands) to determine how many physicians had patients diagnosed with, or suspected of having, a bleeding disorder. “We found Guam had the largest number,” Baker says now.

That day in 1995 an MSS social worker, Roselie “Rose” Zabala, MSW, was calling to tell Baker that a young Guamanian boy had been flown to Hawaii for emergency treatment of a head bleed. “She said, ‘We need help, we don’t understand these disorders,’” Baker recalls. “And I said, ‘OK, I’ll send you an excellent nurse who just started the Hemophilia Foundation of Nevada, and who also has a bleeding disorder. She can educate patients, families and healthcare providers.’”

That day in 1995 an MSS social worker, Roselie “Rose” Zabala, MSW, was calling to tell Baker that a young Guamanian boy had been flown to Hawaii for emergency treatment of a head bleed. “She said, ‘We need help, we don’t understand these disorders,’” Baker recalls. “And I said, ‘OK, I’ll send you an excellent nurse who just started the Hemophilia Foundation of Nevada, and who also has a bleeding disorder. She can educate patients, families and healthcare providers.’”

Regionalization

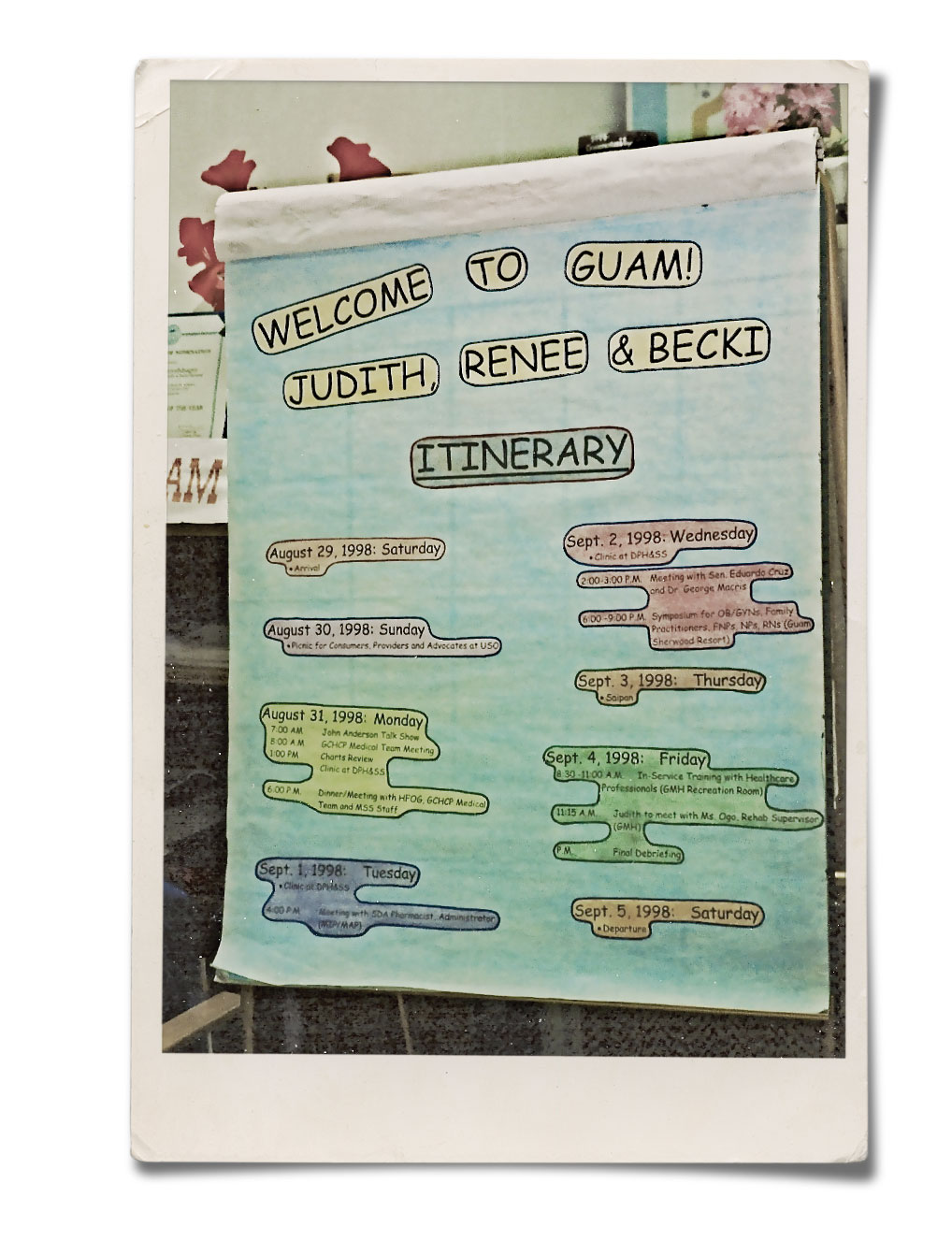

Following the call with Rose Zabala, Baker arranged for the late Renee Paper, RN, CCRN, to make the journey to Guam in 1996. “Renee went to Guam with three objectives: to educate families and clinicians, to see if they were interested in starting a local bleeding disorders foundation and, eventually, a hemophilia treatment center,” Baker says.

Paper hit the ground running and initially helped the local community start the Hemophilia/Bleeding Disorders Foundation of Guam (HFOG), a nonprofit consumer information and advocacy agency. But to ensure that state-of-the-art diagnosis and treatment was available on the island, Guam needed local clinicians to take responsibility for building their knowledge and skills in bleeding disorders. Regionalization was the answer.

To help bridge Guam’s isolation and get the local government health service invested in developing its own HTC, the Region IX network provided mentoring for Guam clinicians. Baker and a group of Region IX HTC clinicians visited Guam in 1997, where they observed Guam’s first pilot comprehensive care clinic and met with government officials.

After its official creation in 1998, with Zabala at the helm as the founding program coordinator, the GCHCP joined the Region IX network. Since then, Region IX has helped GCHCP’s healthcare and social services providers attend conferences on the mainland US. “That’s really critical,” says Baker. “That’s how they continue to remain committed and learn to provide care like their Hawaiian and mainland counterparts—as best they can, given limited resources.”

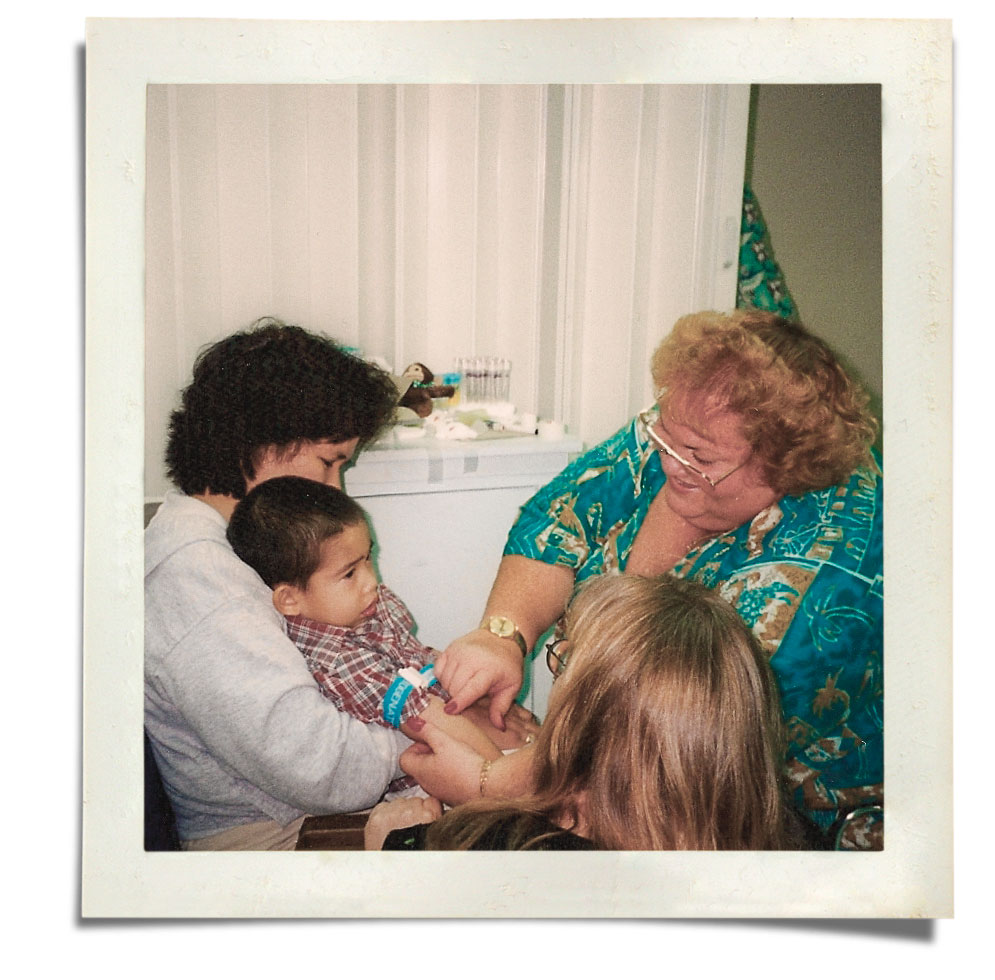

Since 1998, the Guam HTC has raised the level of bleeding disorders care on the island. HTC team members receive training in clinical diagnosis, treatment and health program management. And because the comprehensive care model involves pediatricians, hematologists, nurses, physical therapists, dentists and social workers, as well as school nurses, local ob/gyns and others, the GCHCP hosts an annual islandwide medical symposium to further local knowledge and collaboration. The medical symposium is followed by a family/patient education weekend.

Increasing knowledge, improving care

Better medical care has led to a better quality of life for Guam’s families affected by bleeding disorders. Prior to the HTC, many Guamanians with bleeding disorders missed work, school and social activities because of inadequate treatment. They weren’t living their full lives, says Suzanne Kaneshiro, DDS, MBA, a dentist who is also chief public health officer of Guam’s DPHSS. Debilitating joint pain is one area that’s seen great improvement. “Newer patients aren’t experiencing as much joint pain because they’re on prophylaxis,” Kaneshiro says.

Better medical care has led to a better quality of life for Guam’s families affected by bleeding disorders. Prior to the HTC, many Guamanians with bleeding disorders missed work, school and social activities because of inadequate treatment. They weren’t living their full lives, says Suzanne Kaneshiro, DDS, MBA, a dentist who is also chief public health officer of Guam’s DPHSS. Debilitating joint pain is one area that’s seen great improvement. “Newer patients aren’t experiencing as much joint pain because they’re on prophylaxis,” Kaneshiro says.

Families and individuals are also much more knowledgeable thanks to programs like GCHCP’s annual educational and recreational summer camp. Started in 2001, Camp Hafa Adai helps children and adults with bleeding disorders learn to manage their condition in a fun and supportive environment (Hafa Adai means hello in Guam’s native Chamorro language, and the saying is used on the island in a similar manner as Aloha in Hawaii).

Kaneshiro has experienced the impacts of the Guam HTC programs firsthand. When the GCHCP was in its infancy, Kaneshiro was a young mother and a full-time dentist. Within a short period, her 1-year-old daughter was diagnosed with von Willebrand disease type 3, the most severe form, and extended family members were also diagnosed with VWD. It turned out Kaneshiro and her husband were carriers. When her son was born, he also was diagnosed with VWD type 3.

“Rose Zabala got me through my children’s childhood without any problems, so I really appreciated the HTC program,” says Kaneshiro. “I always had somewhere to go for support and I learned how to manage their disease. It really made my life easier.” In her current role at Guam’s health department, Kaneshiro oversees the HTC. (Sadly, Zabala passed away in May 2018.)

Empowering families and individuals

Former HTC social worker Christine San Nicolas was one of the first to join the HTC. She saw the debilitating effects of bleeding disorders up close, and how the HTC helped families cope. “What stands out about the early days of the HTC is just how well we worked together for the families,” says San Nicolas. “The HTC team became these families’ support system, their advocate and their resource.” For many, it turned their lives around. “The HTC actually changed the hemophilia community on Guam,” says Kaneshiro. “Because of the GCHCP, these people can live normally.” Kaneshiro’s own children have grown and are pursuing dental degrees on the mainland.

San Nicolas recalls how one teenager gained the confidence to take his care into his own hands. “He was very resistant to change or preventive measures, regardless of how agonizing it was for him,” she says. But during a Camp Hafa Adai program, he learned how to self-infuse. “He was so proud,” says San Nicolas. As a result of his experience living with a bleeding disorder, the young man, now a father of a son and two daughters, earned his nursing degree. “He drew his inspiration not only from his experience, but from Renee Paper, who visited Guam often to educate families during those camps,” says San Nicolas.

As for the boy with the head bleed who in 1995 sparked Rose Zabala’s phone call to the Region IX network, for several years following the incident he didn’t attend school, too frightened something terrible might happen away from home. The GCHCP worked with the educational system and his mother to get him back into the school system in 2000. He graduated high school and now works in education. “This same young man who had very little self-confidence eventually became one of our leaders in the HFOG youth group HYPE (Hemophilia Youth Program to Educate) and was the main spokesperson who conducted our media campaigns and outreach throughout the community,” says San Nicolas.

Judith Baker sees the Guam HTC and its place in a robust regional network as a model for other blood disorders, such as sickle cell disease. “Even though Guam is phenomenally isolated and serves a very small population who have a very rare disorder, you can indeed build good services that improve health, reduce costs and improve people’s lives,” she says. “It’s been successful because we focused on the patients and building local expertise.”

A Range of Resources Under One Umbrella

The Guam Comprehensive Hemophilia Care Program (GCHCP) is part of the Western States Hemophilia Network/Region IX along with 13 other HTCs in California, Hawaii and Nevada. The GCHCP provides:

1. Patient registry

2. Monthly clinics for diagnosis and treatment

3. Education and home visits to teach and reinforce medically supervised home therapy

4. Linkage to Guam Public School System

5. Referral network with Public Health outstation clinics

6. Patient data aggregated annually for the national hemostasis and thrombosis data set

7. Staff of family education/recreation camp, Camp Hafa Adai

8. Technical assistance to Guam pharmacists, Medicaid and Medically Indigent Program on cost-effective purchasing of hemophilia medication

9. Tertiary consultation linkage with Kapi‘olani Medical Center, Hawaii

10. Study site for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention nationwide prospective surveillance on hemophilia complications

11. Consultation to Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands