Megan Adediran didn’t understand what was happening. After her son was born, he bled for five days after circumcision. A transfusion of whole blood from her husband finally stopped the hemorrhaging. It would be more than a year and three blood transfusions before Adediran’s firstborn would be diagnosed with hemophilia.

Medical staff did not expect the baby boy to live past age 3. “Hemophilia was like a death sentence,” Adediran recalls from her home in Kaduna, about two hours from Nigeria’s capital city of Abuja. There was no infrastructure on the ground to care for the few children and adults who were actually diagnosed. And medications and supplies to prevent and treat bleeds were severely lacking. “When your child is playing and you’re not sure if he’s going to fall to the ground and bleed in the brain and die, you are living in fear,” Adediran says.

As she cared for her son past his third birthday and thought of the 13 other male relatives who had died from hemophilia-related complications, Adediran decided she needed to do something. In 2005, she established the Haemophilia Foundation of Nigeria (HFN) and registered it as a nongovernmental organization. Adediran is the organization’s founder and president.

At first, Adediran’s goal was simple. “I’ve always said I wanted to give my son a life.” Now the mother of two boys with severe hemophilia A—Timothy, age 20, and Isaac, age 8—she also wanted to give hope to other people in Nigeria with bleeding disorders. To date, only an estimated 268 people there have been officially diagnosed with hemophilia. That leaves thousands potentially vulnerable to complications and even death from a bleeding disorder they may not know they have.

In 2013, HFN partnered with another World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) member organization, the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF), to significantly accelerate Adediran’s goals.

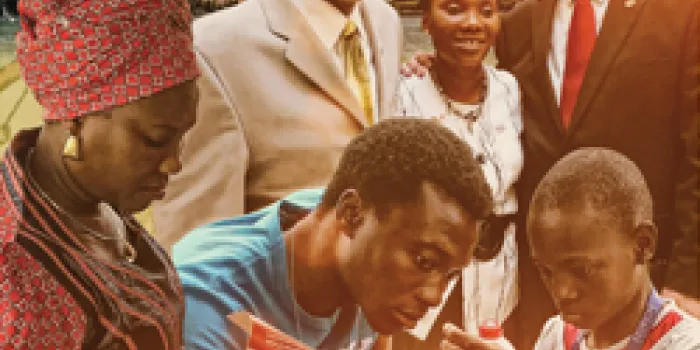

Photo Courtesy of Megan Adediran

Megan Adediran (pictured above, seated in

center) established the Haemophilia Foundation

of Nigeria in 2005

Joining forces

The WFH Twinning Program was established more than 20 years ago. It advances hemophilia care in emerging countries through a formal, two-way partnership. It pairs an emerging hemophilia organization or treatment center with an established one for four years.

“Top priority for the twinning in Nigeria was to build the capacity of the patient organization, help strategize around engaging the government through advocacy and introduce a fundraising strategy,” explains Rana Saifi, WFH’s regional program manager for the Middle East and Africa. “NHF was deemed the best match because of its particular strengths in these areas and its close interest in sharing its knowledge and experience to help.”

“It’s a great honor to be part of WFH’s Twinning Program,” says Val D. Bias, NHF’s CEO. He has hemophilia B. Bias and Neil Frick, MS, NHF’s vice president for research and medical information, have made the 17-hour trip to Nigeria several times. “This is the first time that NHF has had a twinning relationship with another country,” Frick says. “We felt that it was important for us to share the resources we have with organizations around the world.”

The lay of the land

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, is home to more than 177 million residents. The official language is English, but residents may speak up to three additional languages (or one or more of more than 500 indigenous languages). Further, they can be members of more than 250 ethnic groups.

Because populations are diverse, traditions can be as well. For instance, in addition to circumcision, some communities have their infants’ uvulas (the flap of tissue at the back of the throat) removed as a ritual custom. “Babies with undiagnosed hemophilia have died from these procedures without anyone knowing why,” Adediran says.

Obstacles include travel distances and expenses. People generally need to pay out of pocket for any treatments they receive, as government entities (which provide health care in Nigeria) do not currently recognize hemophilia in their policies.

“Nigeria is a difficult country for people with hemophilia at best, and the need is tremendous,” Bias says. He was moved by the economic disparity he saw, recalling the many Nigerian vendors on the sides of roads who sold everything from fruit to furniture to make ends meet.

When the team began to meet with families of more than 100 patients, needs became even clearer. “All the families we met had lost at least one child to a bleeding disorder due to the lack of treatment and diagnosis,” Bias says.

Photo Courtesy of Megan Adediran

As part of the partnership, members of NHF and

the Haemophilia Foundation of Nigeria visited the

National Hospital in Abuja.

Building a network

The improvements in HFN’s ability to provide patient education programs and expand awareness are evident. “It is now the go-to source for all Nigerian patients,” Saifi says. “Its outreach work has ensured that patients in remote areas have access to treatment.” Further, HFN now works closely with about 10 hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs) across Nigeria, she adds.

NHF and HFN collaborated on drafting letters to local, state and federal governments to educate leaders on hemophilia. They also helped strengthen local chapters across Nigeria by providing training on fundraising and board development.

In addition, NHF provided training and needed infrastructure to Adediran’s foundation and to medical staff. NHF also trained a number of clinicians in diagnosis and treatment.

Further, NHF helped craft health messages, including one that explained the importance of the RICE (rest, ice, compression and elevation) method of treating bleeds, particularly in the absence of factor products. “Every patient we saw there had joint bleeds or damage,” Frick explains. “Although the national hospital had outdated equipment, it did have dedicated doctors.”

Some hospitals in Nigeria use supplies donated through the WFH Humanitarian Aid Program, Adediran says. “Despite much progress in the dialogue, there is still some way to go to fully influence the government of Nigeria to recognize hemophilia in its policies and provide treatment products,” Saifi says.

Still, the program’s accomplishments are clear. “The thing I’m most proud of is that more people know about hemophilia than when we first got there,” Frick says. “And progress continues. For instance, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia HTC is now a medical twinning partner for the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital.”

Never-ending relationship

Bias and Frick confirm NHF will continue to be a resource, even when the formal partnership ends. “I’m talking with the NHF Board about providing ongoing support to Nigeria,” Bias says. In addition, NHF is encouraging its chapters to partner with other emerging countries through the Twinning Program. Bias notes that NHF may underwrite some of HFN’s costs.

Adediran is looking ahead to continued work with NHF and continued advocacy in her home country. “Before the foundation, there was no hope,” she says. With NHF’s help, HFN has become a more developed organization. “Through NHF, I’ve become a better advocate to the community,” Adediran adds. “And we’ve been able to develop a lot of education.”

After numerous Skype calls and telephone chats, in addition to in-person visits, the NHF and HFN relationship remains strong. “I admire Meagan Adediran and her husband,” Bias says. He’s impressed that Adediran finances the work of the foundation partly out of her own pocket. “This relationship will never end,” adds Frick. “We’ll always be there to support HFN and its founder.”