Bridget Edwards was diagnosed with a rare bleeding disorder as a newborn, after a routine heel stick wouldn’t stop bleeding. Doctors found that she had afibrinogenemia, a lack of fibrinogen (factor I). This autosomal recessive inherited disorder is so rare, it affects just 1 in 1 million people. Her first hematologist hadn’t treated afibrinogenemia before, so he wasn’t sure what to recommend to Edwards’ parents.

“We learned by trial and error,” says Edwards, 27, of Brewer, Maine. “My parents did a great job. I was never told, ‘You can’t do this, you might get hurt.’”

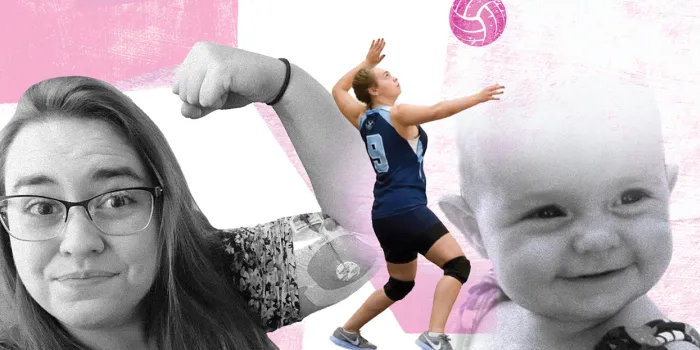

Edwards grew up playing sports, making modifications as needed. She never slid into bases during softball, for example. In high school, she played volleyball, becoming captain of the school team and playing for the Junior Olympic team, which traveled throughout New England.

She wasn’t always happy about the attention she sometimes received because of having afibrinogenemia. When a volleyball injury caused an internal bleed that required frequent infusions, she needed a central catheter. “I received a lot of uncomfortable looks and stares, feeling as though I was being put into a category of ‘she has something that’s wrong with her,’” says Edwards, who noted that sometimes peers had negative reactions. “If I was injured due to an internal muscle bleed and said, ‘I can’t participate in practice today,’ they couldn’t physically see what was wrong. I’d hear, ‘You’re faking it for attention.’”

Growing up, Edwards didn’t know anyone with afibrinogenemia, which was isolating. Going to college inspired her to talk about her condition, raise awareness, and find others who are missing factor I. “Through that, I have met many more people than I ever knew growing up who have afibrinogenemia,” Edwards says. “I didn’t realize, until I went to college, how much I was holding in.”

Sharing her story helped Edwards connect with the Hemophilia Alliance of Maine, where she later worked. She’s currently on its board of directors. “I try as much as I can to encourage more advocacy and awareness about rare bleeding disorders,” Edwards says. “The more awareness that occurs, the more knowledgeable medical providers become, which in turn can make it easier for us living with these rare deficiencies.”

In June 2022, she married Jonathan, whom she’s known since elementary school. “I find that a lot of people with chronic medical conditions can often feel like a burden on their loved ones, as I myself sometimes have, and Jonathan has never made me feel that way. He is definitely one of my biggest supporters,” says Edwards, who has a master’s degree in health psychology and works as a college success specialist for Jobs for Maine Graduates at Eastern Maine Community College.

“No matter what happens to me medically, I never let that impact my ability to succeed,” she says. “I strive to let other people know that even though someone may have a rare disorder, they’re still capable of living a fulfilling life.”

For more information about bleeding disorders in women: Visit Steps for Living and Victory for Women.