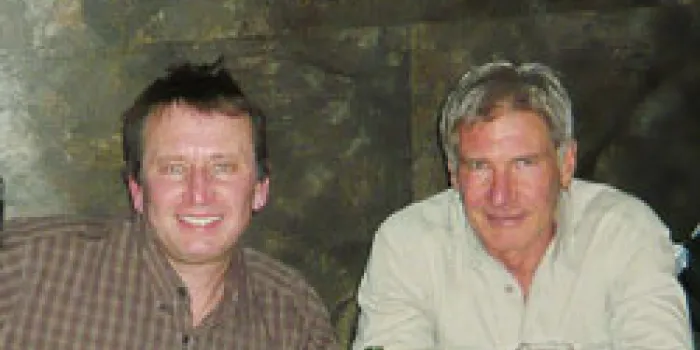

In each issue of HemAware, we “Take 5” with people in the bleeding disorders community and spotlight their efforts with just five questions. Here, we talk to William H. Velander, PhD, chair of the Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Department at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, who met with actor/producer Harrison Ford to prep him for his role as a biomedical researcher in the film Extraordinary Measures.

How did you get involved with the movie Extraordinary Measures?

Harrison Ford, who is the executive producer, and Tom Vaughan, the director of the movie, got together and said they wanted to be sure they gathered the most essential facts about this true story so that when they put together the fictionalized story, they could build some realism into it. The movie is based on a true story of trying to find a way to treat kids who were on the precipice of dying from Pompe disease. The story is about a miracle created through biotechnology, and they wanted to see someone who works in that field. They were interested in learning about discovery medicine, about the process and tensions in going from basic discovery, where a scientist is cloistered like a lonely scribe in a lab for 20 years, and then suddenly has something that could be translatable into a therapy.

Do you feel it was accurate in terms of discovery science?

One thing they did not portray in the movie was that only one therapy is brought forward. With protein therapies—and this is true for hemophilia—different people tolerate different protein therapies differently, some better than others. And there’s only a finite amount of money. Let’s say you have four good therapies that benefit 10%, 20% or 60% of the population, each with a different optimal therapy. They will bring forward the one that benefits 60%, and the other ones will be left on the sidelines.

In your opinion, was the role of the researcher accurately portrayed?

In the movie, the scientist is a crotchety, antisocial type of guy, which, in my opinion, scientists are not. We are, in fact, socially adept. But from the point of view that the science was accurate, and that he had been working on it for 20 years and competing with other scientists, that’s totally true.

Is there a lot of competition among scientists?

By definition, you have competition, and partly because of a finite pool of resources that can be dedicated to bringing a product forward to clinical trial and production. You will see that second place and third and fourth are losers. That was the most poignant part of the movie for me. The researcher’s work was not chosen to go forward, and he had to see the results of four competing efforts and concede that his was not the best. After 20 years of your life, that’s a very disappointing thing. But that’s the way life is in this world of discovery science and translational medicine, where you’re in preclinical animals and then into clinical studies in humans. It’s like a relay race, and sometimes you have to hand the baton off to the next person in the race. That can be painful, because it’s your baby.

Tell me about your current research.

I work with transgenic livestock, animals that are genetically engineered to make human protein—factors VIII and IX—in their milk. I deal exclusively with making an abundance of the protein. When you have intravenous therapy, that’s 100% recovered protein. You get it in your veins, and it’s in. If you try to take any other route other than infusion, you’re going to have tremendous losses. Those losses will amount to 97% to 99%, even in the most optimized formulation when you’re trying to put it in orally or nasally. If you could throw away 99% because it’s made so abundantly and effectively, then you can start thinking about an infant or a toddler or young kid who doesn’t have to inject at all. He can just take a puff or put a paste in his mouth a couple of times a day, and keep his levels above the minimum that he needs to have normal coagulation. That would be a miracle. You can’t do it until you have tons of it to throw away; you can’t even start the experiments. It’s daunting, but if you want to change the quality of life through optimal therapy, that’s what we have to do.