Changing a baby’s diaper is a routine task. Unless your baby is a boy with an undiagnosed bleeding disorder who has just had a circumcision. “There was blood all over the changing table,” remembers Elizabeth Castor. “I was just terrified.”

Elizabeth and her husband, Don, had no previous experience with bleeding disorders. Alexander was their first child, and the pregnancy had gone smoothly.

Following the circumcision, the family rushed the baby to their pediatrician’s office in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, in October 1994. A urologist was consulted, and he recommended more suturing at the circumcision site. Afterward, the baby’s color looked off, says Elizabeth. She and Don were told to admit Alexander to the hospital—the same hospital where he had just spent the past two and a half weeks in the neonatal intensive care unit, recovering from a strep infection he contracted during childbirth.

That night, blood oozed from the circumcision site. The next day more stitching was done. Finally, the bleeding stopped.

But Elizabeth and Don had a nagging feeling something was still wrong.

The journey that unfolded for this family, while unique in its details, is an all-too-familiar one for young couples coping with the news that their child has a chronic illness. The feelings of uncertainty, fear and sorrow that accompany the diagnosis of a child with a bleeding disorder are almost universal among parents. But so, too, are the gradual acceptance of the circumstances and a growing pride in the child and what he or she can accomplish.

The First Diagnoses

For Alexander, the journey to diagnosis was just beginning. His first pediatrician was stumped about what could be wrong. He called for a hematologist, who asked the parents if there were any known bleeding disorders in the family. “No,” they answered. “By now, you would know,” he assured them.

For Alexander, the journey to diagnosis was just beginning. His first pediatrician was stumped about what could be wrong. He called for a hematologist, who asked the parents if there were any known bleeding disorders in the family. “No,” they answered. “By now, you would know,” he assured them.

As the days and weeks passed, Elizabeth and Don noticed something unusual about the baby’s skin. “When we picked Alexander up, he would get little bruises from our fingers on his back and rib cage—not a handprint, but subtle little ones,” says Elizabeth.

When Alexander was six weeks old, the family moved to Peoria, Illinois, where the Castors found a new pediatrician. After taking the baby’s health history, the doctor referred the family to a hemophilia treatment center (HTC). A hematologist there recommended that Alexander be tested for hemophilia.

When the results came in, the family was met at the HTC by the hematologist, a nurse and a medical social worker. All three were sitting down. “Your son has moderate hemophilia,” the hematologist told the Castors.

“We were absolutely in shock,” Elizabeth says. Nothing had prepared them for this news. “My husband played football. I had my wisdom teeth removed. We never had a problem,” she says.

At Alexander’s six-month checkup, the hematologist told the parents that the bruising their son experienced was a symptom of severe hemophilia, so she recommended testing Alexander’s blood again. Once more the results indicated moderate hemophilia. At Alexander’s 18-month checkup, the hematologist told the Castors that she suspected a different diagnosis—severe von Willebrand disease (VWD).

“We had never even heard of von Willebrand disease,” says Elizabeth.

The Final Diagnosis

The third blood test confirmed the hematologist’s hunch—Alexander had type 3 VWD. It also confirmed that the wrong factor product had been used for the infusions Alexander had received until he was 18 months old, once when he had hit his forehead with a rattle and for the bumps and falls that occurred when he was learning to walk.

“I grieved with Alexander’s struggle at birth and in the NICU, and then went through it again with his diagnosis,” Elizabeth says. “I mourned for him the life he would have, filled with needles and joint bleeds. I went through anger at God because I didn’t understand why my sweet boy had to have this chronic disease.”

“I grieved with Alexander’s struggle at birth and in the NICU, and then went through it again with his diagnosis,” Elizabeth says. “I mourned for him the life he would have, filled with needles and joint bleeds. I went through anger at God because I didn’t understand why my sweet boy had to have this chronic disease.”

Back then, there was no EMLA cream to help numb the infusion site. And finding a vein sometimes meant multiple needle sticks. “It broke my heart to watch Alexander endure infusions as a baby,” Elizabeth says. But she and Don insisted on holding their son while the nurse administered the factor product. “We wanted to be calm and strong for Alexander, even though our hearts were being torn up inside.”

On top of the anguish was an all-too-realistic fear. “When Alexander was a baby, I was terrified that he would get a fatal disease from the factor,” says Elizabeth. “The fear would grip me for days.”

Besides feeling fearful, the Castors also felt frustrated. Most of the information they received was on hemophilia. “But that’s not what my son had,” says Elizabeth. “I wanted the name on it—von Willebrand disease.” Their HTC started gathering articles and resources on VWD to share with the family when they came in for clinic visits.

The Family Diagnoses

In 1996, when Alexander was 18 months old, his brother Christopher was born. Christopher’s blood tested negative for hemophilia and his circumcision was routine. “We thought he would be fine,” says Elizabeth. “We had peace of mind.”

In 1996, when Alexander was 18 months old, his brother Christopher was born. Christopher’s blood tested negative for hemophilia and his circumcision was routine. “We thought he would be fine,” says Elizabeth. “We had peace of mind.”

Three years later, sister Natalie was born. A nurse in the delivery room botched the cord blood test, so the baby was not tested for VWD. At about that time, a new hematologist came on board at the local HTC. He was confident that the Castors would know what to look for if Natalie had a bleeding disorder. At age three, she developed frequent nosebleeds and bruising.

The hematologist told them, “You all need to get tested for VWD. I don’t think this is a gene mutation. I think this is type 1 VWD.” But Elizabeth and Don were in denial. “There’s no way,” they thought. “We hadn’t had any problems. Christopher was not showing any symptoms. We don’t need to do this.” The hematologist told them to go home and think about it.

Later, Elizabeth, Don, Christopher and Natalie were all tested. Their blood samples were sent to the lab. All came back positive for type 1 VWD. Elizabeth was floored. At age 34 she was diagnosed with a hereditary bleeding disorder.

It started to dawn on her that she had some of the symptoms of VWD as a girl and later as a woman. Elizabeth had bruised easily as a child and her periods were heavier than other women’s. Next she started to suspect that her father was affected. “My dad bruised easily,” says Elizabeth. “He had nose bleeds. But we all thought, ‘That’s Dad. That’s just the way he is.’” Testing revealed deepening roots of von Willebrand disease in the family tree—Elizabeth’s father and both brothers tested positive for type 1 VWD.

Family Adjustments

Raising three young children with two different bleeding disorders—Alexander with type 3 and his siblings with type 1—was challenging at times. Natalie and Christopher responded well to Stimate nasal spray, so it was kept on hand for their occasional falls and head bumps. But Alexander’s care was more involved. When he needed an infusion, all five family members went to the HTC or ER.

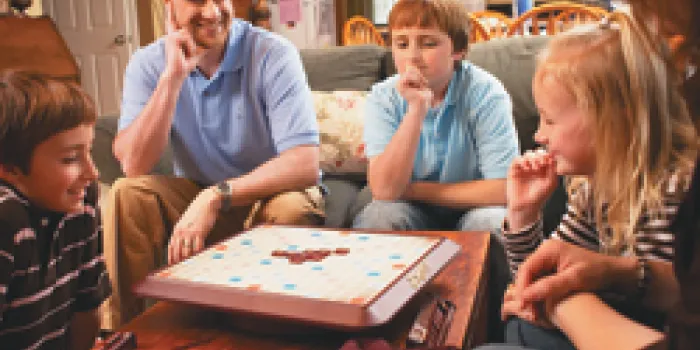

“The ER was disruptive with three children. They were miserable,” says Elizabeth. “It was exhausting.” Further, the staff was not familiar with VWD. Elizabeth and Don then got trained at the HTC so that they could administer Alexander’s factor product at home. Infusion time became family time.

“The ER was disruptive with three children. They were miserable,” says Elizabeth. “It was exhausting.” Further, the staff was not familiar with VWD. Elizabeth and Don then got trained at the HTC so that they could administer Alexander’s factor product at home. Infusion time became family time.

“Christopher, from the beginning, has always been by his brother’s side,” says Elizabeth. “He would feel so helpless during the infusions and wanted to help.” When they were old enough, Christopher and Natalie gathered the infusion materials.

Alexander developed a target joint in his right elbow when he was eight years old, in second grade. He couldn’t throw or catch a ball without spontaneous bleeds occurring. He couldn’t use his right hand to eat or get dressed, and he was having trouble compensating with his left hand. And his schoolwork was affected. “The school would call me to come get him and I would bring him home,” says Elizabeth. “He was in a lot of pain.” At the same time, Alexander was having other joint and muscle bleeds, and severe nose bleeds.

After consulting the hematologist at the HTC, the decision was made to give Alexander a port, a device surgically implanted in the chest to deliver factor product. ”You’re going to love it. It’s wonderful,” Elizabeth was told. “But it was a disaster, a nightmare,” she says. The port was difficult to manage. Even the nurses at the hospital had trouble accessing it. Sometimes the factor backed out of the port and ran down Alexander’s chest, causing a burning sensation under his skin. Even when he was sitting quietly reading a book, he had pain at the site.

After a procedure was done to clean blood clots out of the port, it worked. But 18 months later, while Elizabeth was accessing it for an infusion, the lining tore and the port broke. Alexander’s pain tolerance was fairly high, says his mother, but that day his eyes filled with tears and she knew he was in a lot of pain. Elizabeth took Alexander to the hospital, where the port was removed.

Now the family was at a crossroads. Should they try another port? Was a PICC line (a type of central catheter) the answer? Was it time for Alexander to learn to self-infuse? At this point, Alexander told his parents, “I’m ready. I want to try this.” The summer after he completed fourth grade, when Alexander was 10 years old, he learned to self-infuse at summer camp.

Self-image, Self-disclosure

But summer camp was not the bonding experience with peers for Alexander that it is for many children with bleeding disorders. Some of the boys teased him about having a girl’s disease.

But summer camp was not the bonding experience with peers for Alexander that it is for many children with bleeding disorders. Some of the boys teased him about having a girl’s disease.

“Do I have a girl’s disease?” Alexander asked his parents. “Why is everything we get from the HTC about girls?” His parents reassured him that VWD was not just a girl’s disease and that he was not alone. Still, there were no other boys with VWD at the HTC, in the community or at Alexander’s school. For years, Alexander did not disclose his disorder to grade school friends. Even now, he has told only a select few of his closest friends. His parents make sure he knows that who he is isn’t defined by what he has.

“We tell him, ‘You are not Alexander von Willebrand Castor. You are Alexander who plays the trumpet, enjoys listening to music, enjoys bike riding, is an avid reader, enjoys computers and electronics, and happens to have von Willebrand,’” says Elizabeth.

And both parents try to treat their eldest son as normally as possible. “We don’t hover around Alexander,” Elizabeth says. If he is playing and gets hurt, he infuses and the family carries on with whatever it’s doing. “We don’t let von Willebrand control our lives,” she says.

Sources of Support

Elizabeth describes the first decade of living with VWD as a journey down a long, lonely road. “I wanted to talk to another mom in the same shoes,” she says wistfully. “For 10 years we had no interaction with another parent or boy with VWD,” she says. “That was a very lonely feeling.”

But the void has been filled by others who have come along for the journey. “My family and friends have brought meals to us when Alexander was going through a difficult time,” says Elizabeth. “They have brought thoughtful gifts to Alexander during surgery or when he is on crutches and can’t play.” A medical social worker at the HTC sat with the family for hours in the hospital and clinic. And church friends have been there through it all.

“My Christian friends have played an important part in our lives,” says Elizabeth. The Castors belong to Northwoods Community Church in Peoria. A pastor from the staff has spent time with Alexander. Others support the family with prayers, especially when Alexander has a bad bleed. “The church has been there for us,” she says.

“But still,” she says, “as supportive as they were, it’s not something they knew firsthand.”

Kindred Spirits at Last

At a conference in Arizona, the Castors’ medical social worker met a medical social worker from New York whose caseload included a family with a son with type 3 VWD.

“Alexander was very excited to e-mail another boy who was just like him,” says Elizabeth. Besides swapping stories about rough bleeds and infusions, they share information about their hobbies and interests. “It has been validating for Alexander,” Elizabeth adds.

And the moms have developed a budding friendship, too. “It was an exciting day when I got an e-mail from the mom in New York,” Elizabeth says. “For the first time in 10 years, I had someone who knew what it was like raising a son with type 3 VWD. It has been a wonderful thing for me to have that support.”

Since that initial e-mail, the moms have talked on the phone and they met at a conference in Chicago in the summer of 2006. In October 2006, they introduced the boys at the National Hemophilia Foundation’s 58th Annual Meeting in Philadelphia. When Alexander met the other boy, who is a year younger than he is, it was an “instant friendship,” says his mom.

After all that the Castor family has been through since Alexander’s birth—the misdiagnoses, the problematic port, the family diagnoses—they remain positive. “My faith has put life in perspective,” says Elizabeth. “We don’t sweat the small stuff. We appreciate the small blessings in life. Alexander does have limitations, but there is so much he can do. He can walk, run, play, read and learn. We have a lot to be thankful for.”