Lisa and Michael Louwers are both doctors, but the Farmington Hills, Michigan, couple didn’t know much about hemophilia or other bleeding disorders until their first child was born in March 2010.

After a traumatic delivery that entailed three hours of pushing, manipulations inside the birth canal and finally a cesarean section, baby Colin was born with a pool of blood under his scalp and a diagnosis of severe hemophilia A. “It was a complete surprise since it’s not in our family,” says Lisa, a 31-year-old general surgery resident.

Being doctors helped Lisa and Michael, a 32-year-old resident in physical medicine and rehabilitation, understand the science behind hemophilia. But it didn’t help with the emotions the news prompted. “When it’s your child, it’s very different from when it’s your patient,” says Lisa. “We went through a lot of the same things other parents go through.”

Fortunately, the Louwers family didn’t have to go through the experience alone. As it turned out, the hospital where Michael works is home to one of the federally funded hemophilia treatment centers (HTC) that provide comprehensive care to individuals with bleeding disorders and their families. The University of Michigan Hemophilia and Coagulation Disorders program in Ann Arbor quickly made the family feel less isolated.

“Part of the huge benefit of being part of an HTC is that it has monthly gatherings for parents,” Lisa says. The dinners include speakers on topics such as dental issues. “You have the opportunity to talk with other parents who understand what you’re going through—something that creates a real sense of community.”

The center sent a nurse and social worker to the Louwers home to meet with their extended family and friends. “They were there for three hours explaining hemophilia—the genetics of it, the symptoms, what to look out for,” remembers Lisa. The pair even went around the house looking for ways the new parents could make their home safer, such as extra padding under rugs. That was in addition to the medical care Colin receives at the center. “The HTC is such a fantastic model, because it feels like you’re calling a friend,” says Lisa. “The staff are always available and willing to go the extra mile to help.”

The Louwers family’s experience is fairly typical. HTCs are designed to attend to all of a patient’s needs, from the medical and psychological to practical matters such as schooling, insurance and jobs. Research shows this holistic approach works, giving patients with bleeding disorders longer, healthier lives.

[Steps for Living: Understanding and locating HTCs and Jobs & Careers]

Comprehensive Care Model

HTCs were created because people with bleeding disorders, their families and healthcare professionals demanded them. In 1973, the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF) launched a two-year campaign to establish a nationwide network of centers to diagnose and treat hemophilia and other bleeding disorders. The goal was to provide an extensive range of coordinated services for patients and families within a single facility. Today, there are approximately 141 treatment centers and programs across the country. The HTC network is partially funded by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, and other federal agencies.

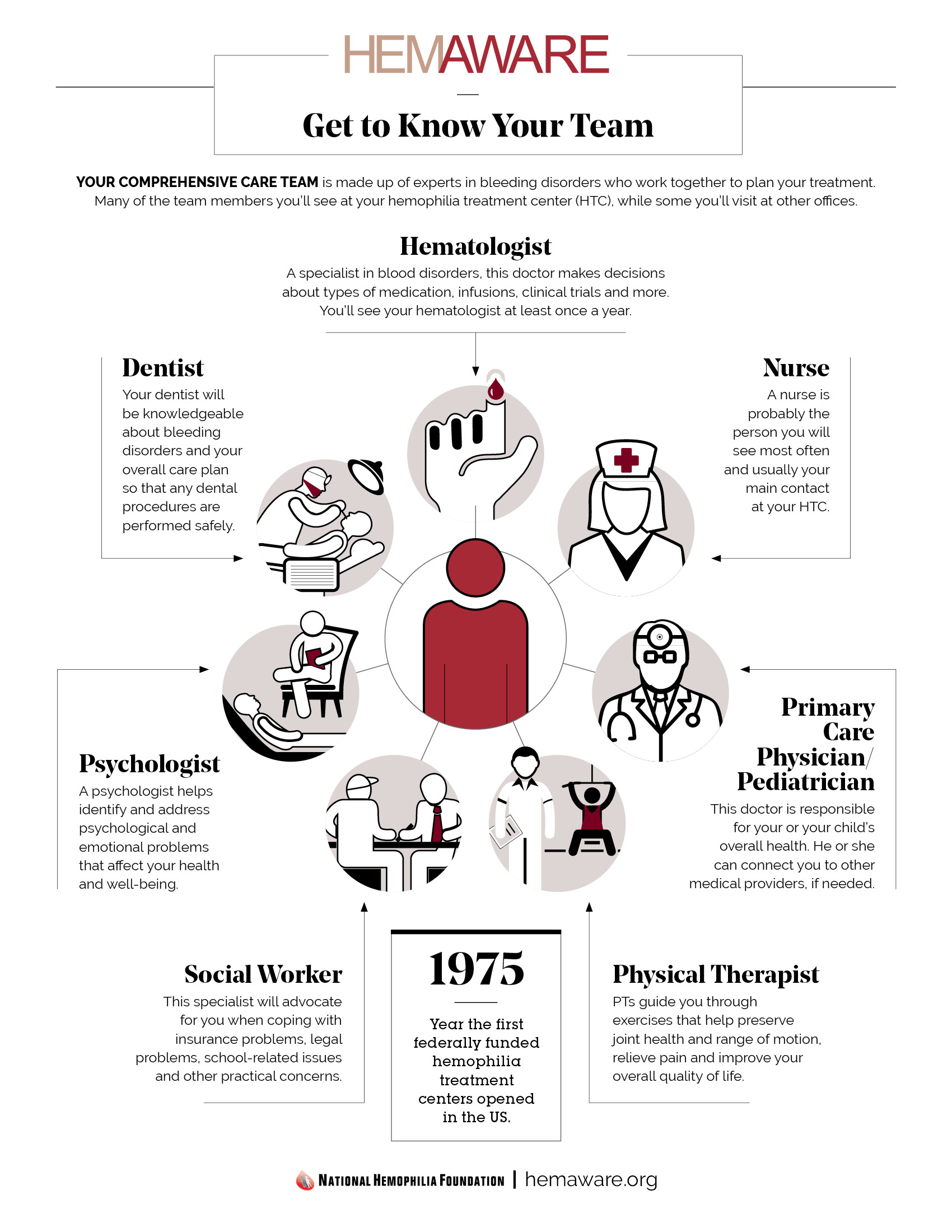

What each HTC has in common is a comprehensive model of care. HTC treatment teams typically include hematologists, pediatricians, nurse coordinators, social workers and physical therapists. Some centers also have orthopedists and dentists on staff.

In addition to providing specialty care, the team can also work with a patient’s regular physician, dentist or specialist. Some pediatricians hesitate to immunize to children with bleeding disorders, says Alice Cohen, MD, director of the Comprehensive Hemophilia Treatment Center at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center in New Jersey. “We’ll help them safely administer immunizations,” she says. HTCs can also provide education and support to physicians who perform cardiac testing, colonoscopies or other services in adults.

Cohen recommends that her patients come in at least once a year for a comprehensive evaluation and as needed in between. “Our nurse fields calls all day long, helping families with everything from how to open a factor bottle to deciding whether a child needs to be seen,” she says.

Cohen’s HTC provides emergency care during office hours. A physician is on call 24 hours a day to address concerns or coordinate treatment when a person is en route to the emergency room (ER). The HTC also makes sure patients have clotting factor on hand at home in case they need to use it in an ER. “They can bring factor with them because sometimes hospitals won’t have clotting factor on the shelf to give to them,” says Cohen.

Some HTCs are portable, serving patients via temporary traveling clinics in local hospitals before moving on. If you’re planning a trip, your HTC staff can contact their counterparts in other parts of the country or world to let them know you’ll be traveling there and may need assistance.

Education Emphasis

HTCs provide more than just treatment, Cohen says. “One of the major roles of the HTCs is education,” she explains. When children begin prophylaxis treatment, for example, HTCs will teach parents and caregivers, and, eventually, the children, how to infuse themselves so they can treat at home. This can save time, reduce discomfort and increase convenience during a bleed, because patients don’t have to travel to an emergency room and wait, she adds.

[Steps for Living: Treat Responsibly Today for a Healthy Tomorrow]

The educational role extends beyond the patient and family. HTC staff often visit schools, explaining to teachers, staff and school nurses what hemophilia is, what activities a child can engage in and how to recognize an emergency.

This comprehensive approach to care does more than improve the quality of life for people with bleeding disorders. According to studies by the CDC, people with hemophilia are 40% less likely to be hospitalized for bleeding complications if they use HTCs rather than receiving care elsewhere (see “Learn More”). Those who use HTCs are also 40% less likely to die of hemophilia-related complications. The comprehensive care approach is so effective that the federal government is considering HTCs as a model for care for diabetes, sickle cell anemia and other diseases. The new buzzword on Capitol Hill is “medical homes,” something individuals with bleeding disorders have long enjoyed.

Psychosocial Needs

HTCs also address psychosocial needs. “We’re there to make sure the whole person is taken into account all the time,” says Mary Jane Berry, MSW, a clinical social worker at the Georgetown University Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center in Washington, DC.

During the comprehensive care clinic appointment, Berry schedules a short visit with each family to introduce herself and ask if the family needs help with insurance matters. She also screens patients about their coping strategies, pain management and any job-related, marital or other problem. If parents are worried about how to manage their insurance copayment, for example, Berry can connect them to their state’s Children’s Health Insurance Program. If a marriage is in trouble, she can provide basic counseling. Berry also meets with siblings, focusing on such issues as sibling rivalry, guilt or caregiving. In addition, HTC social workers can provide referrals to various helpful agencies in the community.

Berry also sees patients and families during their routine visits in the clinic for medical care. “I poke my head in and ask a few questions, which breaks the ice,” Berry says. “Maybe they don’t need anything. But if there’s a job change or an insurance change or something else comes up, then they know my face.”

HTC social workers can also help people with bleeding disorders help each other. At Georgetown, for instance, Berry runs a monthly men’s group she describes as “mutually supportive.” Although it arose more than two decades ago out of patients’ desire to discuss issues related to HIV and hepatitis C infection, the discussion today ranges more broadly. “We talk about anything and everything, from parenting and grandparenting to careers and retirement,” says Berry. Parent and sibling support groups are also common at HTCs. And many centers work with the local hemophilia chapter to hold summer camps for kids and retreats for parents.

Becoming an Insider

Tom Wilmarth, 36, of Rochester, New York, knows firsthand just how supportive an HTC can be. When his son, John, got his routine infant immunizations five years ago, the baby’s body developed some strange bruising and bumps. Then a blood test caused his hand to swell up and turn blue. The diagnosis was severe hemophilia B.

“My wife and I had heard of hemophilia and knew it was some kind of bleeding disorder, but that was about the extent of our knowledge,” says Tom, now vice president for public policy at the Mary M. Gooley Hemophilia Center. “The doctor said, ‘If you’re going to have a child with hemophilia, one of the best cities in America to live in is Rochester because of the Mary M. Gooley Hemophilia Center.’” Tom and his wife, Annaliese, a special education teacher, quickly found out why.

“You have this comprehensive care model that can address all the things that can affect your life with this medical condition,” Tom says. “To have a place that goes above and beyond what they need to do to treat the medical condition is unexpected, refreshing and reassuring.”

John gets a comprehensive assessment from the center’s annual clinic, where he’s thoroughly checked out by a doctor, physical therapist, orthopedic surgeon, dentist and other healthcare professionals. In between, he visits the center twice weekly for prophylactic factor infusions. “Putting a needle in a vein can be a pretty traumatic experience, both for the child and the parents,” says Tom. He will soon undergo training to infuse John at home. “But the center has done a great job making John feel comfortable.”"

The center—which is a combined HTC and NHF chapter—features a playroom with books and toys and a welcoming staff. There are even holiday parties—part of the reason John’s 8-year-old sister, Emily, likes to visit the center.

A year after the family first came to the center, Tom was invited to join its board of directors. When a staff member quit, Tom jumped at the chance to raise funds and the center’s profile. “Even beyond HTCs, I’m promoting this model of care,” he says. “It’s a message of comprehensive care that can cut costs and help people improve their physical and emotional health.”

[Download - Hemophilia-Care-Team]