The National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF) celebrates its 75th anniversary in 2023. Throughout the year, HemAware.org will be commemorating this special milestone with articles that look back at notable programs, initiatives, and events in NHF’s history.

The adage that “all politics is local” is accurate enough, but it only hints at a broader truth: Ultimately, all issues — whether educational, environmental, or medical — are local, or even individual.

That’s because the human brain analyzes most problems through the lens of immediate personal impact, a tendency requiring national organizations, including advocacy and support groups like the National Hemophilia Foundation, to establish and maintain individual connections to succeed.

An understanding of that truth is evidenced in the foundation’s support of a nationwide chapter network and embedded in its DNA.

It was begun in 1948 by Robert Henry and his wife, Betty Jane, who were struggling to help a son with hemophilia and had grown frustrated by the lack of treatment options as well as the all-too-short life expectancy for people with the disorder at the time: about 24 years.

They designed the foundation to bring together families facing similar challenges so they could support and learn from each other. Eventually, the group expanded to include doctors and researchers, and parents of children with hemophilia around the country began setting up chapters in their own communities.

Since blood transfusions were the only treatment for hemophilia back then, the local chapters organized blood drives. They also raised money, educated their communities about the disease, and urged doctors and researchers to find a cure.

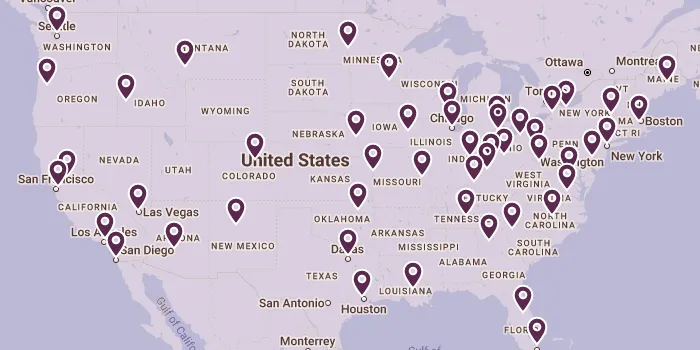

Today, there are more than 50 chapters around the country working with people who have a variety of bleeding disorders, from hemophilia to von Willebrand disease, rare factor deficiencies, and platelet disorders.

It’s the chapters “that are carrying out NHF’s mission at the local level,” says Kristi Harvey-Simi, the foundation’s senior director of chapter training and advancement. “As a national organization, we don’t know what’s necessarily best in every community, but the chapters do. They know what the families with bleeding disorders are dealing with in their area.”

Indeed, Sue Martin, executive director of the Bleeding Disorders Association of South Carolina, describes the group as the national organization’s “boots on the ground” in the state. “The impact of the work we do every day is measured in the sincere thanks we receive, showing the importance of walking together with those affected, assuring them they are not alone in their bleeding disorders journey.”

The Importance of Grants for Local Chapter Efforts

To ensure local groups have the information and tools they need, NHF has been providing financial grants and support through its Access to Care Today, Achieving Cures for Tomorrow (ACT) Initiative, launched in 2008.

Since then, the number of NHF chapters has increased more than 50%, and almost all of them have paid staff, compared with just 20 when the initiative began. The two-year grants supporting the creation of those positions have a unique structure: They provide full funding for the first year and half the second year, with chapters soliciting donations to fill in the gap.

The goal is ensuring that chapters can sustain staff positions once the grant expires, the foundation says.

NHF’s chapter services department also works with local organizations on building effective boards of directors, diversifying revenue sources, staying abreast of the latest treatments and technologies, and supporting advocacy efforts.

“We have a wonderful advocacy team that really helps chapters look at what’s happening locally with issues such as access to care and drug formularies, advocate for changes in state law, and cooperate with other organizations to obtain the best treatments for people with bleeding disorders,” Harvey-Simi says.

Building diverse boards is an important step toward boosting local chapters’ effectiveness, she adds.

“In the past, board members have largely been people impacted by a bleeding disorder, and many still are,” Harvey-Simi explains. “They’re the face of the organization, the ones out there talking about its mission and how it helps people with bleeding disorders.”

For nonprofits, however, it’s also helpful to have board members from a variety of backgrounds, including healthcare providers, marketing and communications specialists, lawyers, social media experts, and people with extensive fundraising contacts.

“We help chapters analyze their current board makeup and identify gaps,” she explains. Providing that kind of support enables local chapters to focus on their priorities, which is why NHF set up its chapter services department in 2008.

While the national organization can help with administration and research, “it’s really the chapters that are out there serving the people with bleeding disorders and providing the education,” Harvey-Simi says.

The Western Pennsylvania Bleeding Disorders Foundation, for example, has delivered over $65,000 in direct patient assistance to community members in need and hosted 29 educational programs at no cost to them over the past fiscal year, says Executive Director Kara Dornish.

“Because bleeding disorders impact nearly every area of our members’ lives, we strive to provide relevant and timely information about everything from raising affected children to dealing with financial stress to joint health and treatment concerns and much more,” she says.

The Impact of Local Bleeding Disorder Chapters

The results of such efforts are what motivate local staff and volunteers to keep striving for improvement.

“Seeing the positive changes, improved health outcomes, and increased quality of life in the community is rewarding and fulfilling,” New England Hemophilia Association Executive Director Rich Pezzillo explains. “It reinforces to our staff, board, and volunteers our deep commitment to the mission of the organization.”

Local chapters “are the people connecting individuals with a rare disorder to other individuals, creating friendships, and creating community for people who have never met another person with a bleeding disorder,” Harvey-Simi says.

Those connections can be life-changing. Harvey-Simi recalls meeting a boy who had come to a chapter event in Hawaii for the first time, didn’t know anyone, and felt uncomfortable. “Within 15 minutes,” she says, “these boys just embraced him, and they were running, playing hide-and-seek, and talking.”

Angellica Kelley had a similar experience when she went to Camp Bold Eagle in Michigan for the first time at age 11, after her diagnosis with von Willebrand disease.

“I had never met someone with a bleeding disorder, so this was all new to me,” says Kelley, who now serves as the associate camp director for the Hemophilia Foundation of Michigan.

“I remember vividly climbing on the charter bus on the way to camp, looking around, and not knowing anyone,” she recalls. “This little blond girl walked up and sat next to me, and that was it. We were best friends.”

On the way home from camp, when Kelley left the bus first, her new friend followed her out. “We were hugging each other and crying like we never wanted to leave,” she says. “I knew I would go back to that camp as long as I could because it’s a whole different world.”