Despite the commercials on TV, osteoporosis—a disease characterized by weak, brittle bones—doesn’t just occur in older women. When Joe Nozemack, a publisher in Portland, Oregon, fell in the bathroom, he sustained a hairline fracture in his left hip. A bone scan showed that he had osteoporosis. He was 33. “I was not too surprised,” says Nozemack, now 41. Difficult-to-treat childhood bleeds from his severe hemophilia A and inhibitor led to target joints in his elbows and knees. Consequently, Nozemack wasn’t very active. “One of the things that generates the bone density is activity,” he says.

There may be a connection between hemophilia in men and earlier onset of osteoporosis. Further, having the added diagnoses of HIV and hepatitis C may also contribute to loss of bone density. Until there are more clinical trials on men with hemophilia, the exact causes of their osteoporosis remain uncertain. Without standards of care, there is no clear consensus on screening and treatment. Still, staff at hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs) across the country are discussing bone health in their clinics, making individual recommendations for their patients and conducting studies to advance knowledge in this area.

The Bone Bank

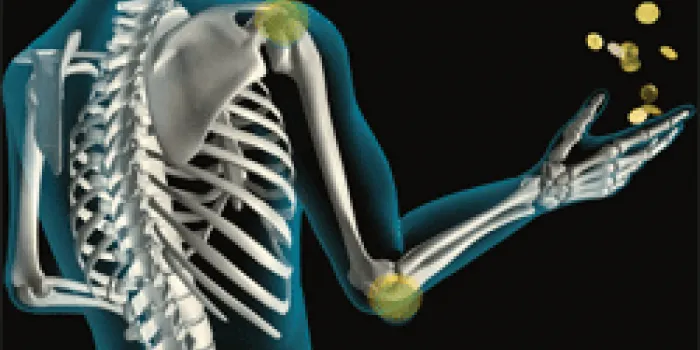

The bones in a human skeleton appear hard and solid, but in a living person they’re in a constant state of motion. Like a bank account, your body tries to keep a balance between deposits of new bone and withdrawals of old bone. Osteoblasts make the deposits by forming new bone cells called osteocytes; osteoclasts, which break down bone tissue, make the withdrawals. Growth, maintenance and repair of bone are influenced by several hormones, including parathyroid hormone (PTH).

Science Photo Library/Glow Images

Vitamin D helps your body absorb calcium, a mineral that is one of the main components of bones. (See “Bone Up,” HemAware Spring 2011, page 10.) If you’re not getting enough dietary calcium, PTH stimulates the osteoclasts, and more is withdrawn from your bones and deposited in your bloodstream. This process is called resorption. If this cycle continues unchecked, you can develop osteopenia (lower bone mineral density) and eventually osteoporosis.

Primary osteoporosis is an age-related condition occurring in women after menopause and men after age 70. Secondary osteoporosis, in contrast, can occur much earlier in association with certain diseases, medications and/or lifestyle behaviors. Further, osteoporosis may have a genetic link, as it tends to occur in families. Hemophilia can predispose people to have weakened bone, as can certain medications, including immunosuppressants used in organ transplant recipients. Lifestyle behaviors that contribute to the risk include alcoholism, smoking and inactivity.

Thin, weak bones break more easily. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF), one out of five Caucasian men experience an osteoporosis-related fracture, usually in the hip, spine or wrist.

Osteoporosis is confirmed via the axial, or central, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) test. DXA uses a scanning arm to send radiation into your skeleton, taking measurements of the hip and spine, and sometimes the top of the femur (thigh bone).

Hemophilia and Bone Health

Before prophylactic therapy with drugs, older patients with hemophilia had few options. They routinely experienced joint and muscle bleeds that were painful and resolved slowly. Bob Harris, 62, a retired 8th grade history teacher from Rome, Georgia, had a childhood marked by ankle and knee bleeds. “We waited until I had swelling, stiffness and pain, then my doctor would give me whole blood,” he says.

Alexander Raths/Thinkstock

During critical periods of bone development in childhood and adolescence, many of these men spent long periods resting in the hospital or at home. Consequently, their bones paid the price. Harris, who wore leg braces in elementary school, ended up in a wheelchair by sixth grade. “Inactivity or decreased activity, along with less weight-bearing exercise, contribute to decreased peak bone mass, which you need to get by about the age of 20,” says Mindy Simpson, MD, pediatric hematologist/oncologist at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. “This can set these patients up for an increased risk of osteoporosis, even later in life.”

In 2007, Dr. Thomas Wallny of the University of Bonn, Germany, and colleagues published a study on osteoporosis in men with severe hemophilia in Haemophilia. Of the 62 subjects, 43.5% had osteopenia and 25.8% had osteoporosis. The authors concluded that multiple joints affected by bleeds, accompanied by muscle atrophy and loss of joint movement, were associated with lower bone mineral density in the hip.

In 2012, Christine Kempton, MD, MSc, assistant professor, Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center of Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, and Department of Hematology/Oncology, Emory University, conducted a study of 88 men with hemophilia to determine their bone density. DXA scans of the femur were used in the analysis. The median age of the men was 41; the youngest subject was 25. “We wanted to evaluate men who were already at or past their peak bone mass,” she says. The findings revealed that 38% of the men older than 50 had osteoporosis. Another 42% in that age group had osteopenia. “Overall, what was striking was the proportion of men above the age of 50 who met the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for osteoporosis,” says Kempton.

The prevalence of osteoporosis in men with hemophilia is startling when compared with their peers. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collects data on bone mineral density through its National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Results are obtained through DXA scans of the femur and spine and through interviews. They show that osteoporosis occurred in only 3% of men 50–59, 3% of men 60–69 and 4% of those 70–79—a far cry from Kempton’s double-digit results.

The Roles of HIV, HCV or Both

Men with hemophilia who contracted HIV and/or hepatitis C virus (HCV) from contaminated blood products two to three decades ago are at increased risk of osteoporosis.

According to the NIH, men with HIV are four times more likely to develop osteoporosis than their unaffected peers. The cause, however, is not clear. Some blame anti-retroviral therapies (ARTs) used to treat HIV; others blame the virus itself. In a 2011 study in AIDS Reviews, Spanish researchers Felix Gutierrez and Mar Masia discovered that certain ARTs accelerate the loss of bone minerals during the first couple of years on the therapy. They hypothesized that the mechanism was either a direct action of the drugs on bone cells or an indirect action through the loss of phosphate by the kidneys. One type of ART, protease inhibitors, may block the conversion of vitamin D into its active form.

The link between osteoporosis and HCV is also not completely understood. “Osteoporosis is a complication of end-stage liver disease,” says Margaret Ragni, MD, MPH, professor of medicine in the Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology/Oncology at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania. The damaged liver cannot convert vitamin D to its active form, so calcium is not absorbed properly. Studies show that cytokines, chemical messengers that help regulate the immune response to disease and infection, are involved. “Cytokines can be measured in livers and plasma of patients with hepatitis C,” says Ragni.

The common denominator among patients with elevated cytokine levels and who also have chronic HIV, HCV, chronic anemia or metabolic disorders is long-term chronic infection. Cytokines are believed to contribute to osteoporosis by increasing the rate of bone resorption by osteoclasts. But the process is still unknown.

“We need more data from observational and case-control studies to determine the mechanism of osteoporosis in HIV/HCV infections, and the best approach to reducing and preventing it,” Ragni says.

Bone Density Testing

If you have hemophilia, bone density testing probably should occur sooner rather than later. “I think it’s appropriate, based on my study and the rest of the literature, that men over the age of 50 should have a screening DXA, regardless of any other co-morbidity, their joint disease or severity of hemophilia,” says Kempton. An unexplained broken bone in a younger man could also move up the DXA date. “The presence of a low-trauma or spontaneous fracture clearly is a red flag,” she says.

“The bone DXA scan is really simple. It takes 10 minutes, it doesn’t hurt and there’s very minimal radiation,” says Simpson. “There’s not a better test available.”

Bone mineral density is then determined using a formula developed by WHO. Results are given in standard deviations from the norm. Using that information, your doctor can tally your FRAX score, your risk of hip fracture and fracture of other large bones within the next 10 years.

But without formal recommendations, your hematologist may follow a different path. For instance, you may be referred to an endocrinologist or rheumatologist.

Building Your Bone Savings Account

Jupiter Images/Thinkstock

The current treatment for osteoporosis encompasses improved diet, the use of supplements, lifestyle changes and medication. NOF estimates that men over 50 consume less than half of the recommended daily dose of calcium. Further, older people produce less of the active form of vitamin D. According to the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of calcium for men ages 51–70 is 1,000 mg a day and 1,200 mg if you’re 71 or older. The RDA of vitamin D for men is 600 IU (international units) if you’re 51–70 years old and 800 IU if you’re 71 or older. Dairy products, fish and foods fortified with calcium and vitamin D are your best dietary assets. Supplements can help make up the difference, but talk to your doctor first. Some supplements, such as those containing fish oil, thin the blood and are not recommended for patients with bleeding disorders.

Bisphosphonates are FDA-approved drugs prescribed to treat osteoporosis. They inhibit osteoclasts from breaking down bone tissue, increasing density and making bones stronger and less prone to fractures. In 2012, Harris was diagnosed with osteoporosis by his HTC. The staff referred Harris to a rheumatologist, who prescribed a bisphosphonate. “He put me on a generic of Fosamax on a weekly basis,” says Harris.

Your hematologist may suggest these lifestyle changes to benefit your bones: Stop smoking, limit alcohol consumption and increase daily exercise. In some cases, physical therapy (PT) may be recommended. “Most studies have shown that doing the weight-bearing or strengthening type of exercise can have a modest improvement in bone density,” says Angela Forsyth, PT, DPT, at the Rush HTC in Chicago.

Lifting weights can also help. “When you do weight training in a controlled and safe manner, it places the kind of stress we want on the bones to help improve density,” Forsyth says. Nozemack hired a personal trainer in 2010. Since then, he has been working out regularly on the free weights and machines at his gym. Already he has seen improvements. “I have gained strength and way more muscle mass,” says Nozemack. “I can do stuff that I never would have thought of doing before.”

Even simply strolling through your neighborhood can build bones. “Walking is an impact activity because you’re putting your foot on the ground,” Forsyth says.

Men with hemophilia who haven’t been diagnosed with osteoporosis can start building a savings account in the bone bank. “Encouraging normal, healthy weights, good activities and being able to get people to their peak bone mass early in life can set them up for much better bone health later on,” says Simpson.