More than a quarter of the bleeding disorders population in the US relies on Medicaid to pay health expenses. Medicaid, a government health program for low-income Americans, is a federal-state partnership. That means the federal government provides guidelines to follow, and states administer their individual programs.

Changes are afoot with this program, and they may create barriers to accessing clotting factor for some people. Here is what you must know and what the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF) is doing to advocate for you.

Under the magnifying glass

Just as all people have to be vigilant about their finances, state governments must find ways to stay within their budgets. “Unlike the federal government, local governments must have a balanced budget,” explains Michelle Rice, NHF senior vice president for public policy and stakeholder relations.

Medicaid is a large part of every state’s expenditures, comprising about one-quarter of total state budgets in 2013. That makes it a target for scrutiny. “It’s important that patients understand these changes are not directed at one condition over another,” says Marla Feinstein, NHF public policy analyst. “They’re directed at controlling costs.”

One option Medicaid programs don’t have that private plans do is asking patients to pay more. “Under Medicaid, there are stricter rules about what a patient’s out-of-pocket expenses can be,” says Johanna Gray, senior vice president with CRD Associates in Washington, DC, and a federal policy adviser to NHF.

But Medicaid programs do have a few cost-cutting options. “They’re either going to lower reimbursement, narrow networks or set up restrictive formularies,” Rice says. “In some cases, they’ll try to do all three.”

Maxuser/ThinkStock

Restrictive formularies

Therapies to treat bleeding disorders are expensive, and costs are expected to rise. One obvious place for a state Medicaid plan to find savings is on its drug formulary, the list of all the drugs that it “covers,” or pays for. If a drug is not on the list, the plan does not pay for it.

“Before, state Medicaid plans tended to include all types of clotting factor on their formularies,” Gray says. Now, plans are being more restrictive about what’s on the formulary. This is especially problematic for patients with bleeding disorders because they often respond better to one therapy over another. “It’s a very unique disease. There’s not a one-size-fits-all treatment or even a three-sizes-fit-all,” Rice says.

A second concern is that formularies can be divided into preferred drug lists (PDLs). A PDL explains the level at which each drug is covered, typically organized by tiers. “Tier 1 means generic, tier 2 means preferred and tier 3 means nonpreferred,” Rice explains. “As you go up the tiers, the amount of your copay increases.” Some formularies include a tier 4, or specialty tier, in which patients pay a percentage of the drug’s cost, called coinsurance. Because drugs to treat bleeding disorders are pricey, coinsurance amounts on them can be astronomical. NHF has been largely successful at keeping clotting factor drugs out of specialty tiers, Feinstein says.

In some Medicaid plans, the difference between tiers isn’t monetary, but rather the type of approval you need. “You may have to get a prior authorization more often, or you may need a more detailed prior authorization,” Rice says. “Some of them put more hurdles in place to access one of the newer, extended half-life drugs.” Drugs with a longer half-life allow some patients to infuse less often.

The structure of a PDL encourages patients to opt for drugs from the lower tiers, ideally the tier 1, generic medications. “For most drugs, that’s fine because there are generics available. But there are no generic clotting factor products,” says Feinstein. In the past, there were fewer distinctions made between preferred (tier 2) and nonpreferred (tier 3) drugs for bleeding disorders because there were simply fewer drugs around. “Now, with the availability of more drugs and many more in the pipeline, PDLs are the only way for insurance companies to control costs,” Rice says.

NHF’s position:

NHF maintains that all FDA-approved therapies to treat hemophilia, von Willebrand disease and related bleeding disorders should be included on a health plan formulary, Rice says. Cost should not be the sole determining factor in where a drug is placed within the formulary. Clinical outcomes and patient need should be considered. If drugs are classified among preferred, nonpreferred and nonformulary tiers, there should be a clear, direct, timely process (a medically necessary exception provision) for the patient and his or her physician to follow to get the patient the needed drug. That process should not include the requirement that a patient first “fail” on another drug.

Restrictive provider networks

To control costs, some plans restrict their provider networks, particularly their pharmacy networks. In essence, your choice of pharmacies is limited to the few that carry factor and are also in your insurance plan’s network. Gray notes that the number of pharmacies carrying clotting factor is already small. “We’re living in a world where everything is getting narrowed,” she says.

NHF’s position:

There should be more than one qualified specialty pharmacy provider in a network. Preferably, there should be a specialty pharmacy option and one 340B option.

Potential changes to reimbursement

In the next year, states will change the way they reimburse for drugs. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced a rule in January regarding reimbursement for retail pharmacy outpatient drugs (anything not considered a specialty drug). “The federal government is telling states that they need to reimburse based on what the pharmacy providers spent—their acquisition cost—plus a dispensing fee,” Gray explains. “States have flexibility in setting the dispensing fee.” They have until April 2017 to decide how they’ll change their policies to comply with the new rule. Currently, states are determining what is a reasonable approach for clotting factor. “We are being hypervigilant with respect to these changes so they don’t affect patients’ access,” says Feinstein.

NHF’s position:

NHF does not suggest or recommend a specific drug price. Instead, reimbursement should be reasonable and adequate so as not to impede patient access.

How NHF is advocating

NHF monitors and tracks legislative and regulatory actions in all 50 states. When Rice’s team learns of potential changes to a Medicaid program, it drafts a letter to state Medicaid officials. The letter explains any concerns, includes NHF’s pertinent position statements and requests a phone conversation or in-person meeting.

NHF often involves other stakeholders in the process. “We will typically reach out to the chapter in that area and ask it to sign the letter with us,” Rice says. NHF may invite a representative from the chapter to join in-person meetings with representatives from the Medicaid plans. Chapters and hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs) can help coach patients and physicians who are willing to share their powerful stories. When the changes under consideration have a detrimental impact, a local legislator may be involved as well.

During meetings, NHF provides education about bleeding disorders and strategies that have been effective in managing costs. “Keeping people with bleeding disorders healthy is the best strategy,” Gray explains. For example, access to HTCs and clotting factor therapies without delay save costs in the long run, she adds.

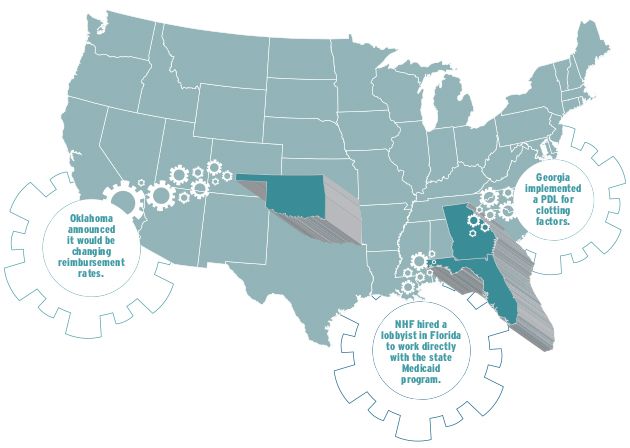

Advocacy in three sample states

For years, Medicaid patients in Florida were subject to a very restricted network for pharmacy providers. When the agency started the bidding process for new providers, NHF took action. “We hired a lobbyist in that state to work directly with the state Medicaid program to share our concerns about the size of the network and the contract requirements,” Rice says. “We felt that very few people could even meet their requirements to apply to provide factor.” The lobbying work was successful, and NHF’s suggested alterations were made.

The Medicaid program in Georgia implemented a PDL for clotting factors, significantly reducing the number of drugs in the preferred category. “We explained what our concerns were, and they agreed to grandfather everybody who was currently on a product,” Rice says. Georgia also created a very clear process by which a patient can access a nonpreferred drug.

Oklahoma announced it would be changing reimbursement rates, creating a PDL and establishing requirements that pharmacies had to meet to be an authorized Medicaid pharmacy. Officials clearly explained how to access therapies from the various tiers and what documentation would be necessary. “While it was a lot more rules than were in place before, we felt the treatment center was comfortable with what was going to be required,” Rice says. She and her team ultimately wrote a letter commending the state for being proactive. “We want to make sure they know that we are supportive,” Rice says.

Healthcare expenses are a big part of life when you have a bleeding disorder. As an informed consumer, understand your benefits and know your options. Meanwhile NHF will continue staying ahead of policy shifts to make your personal advocacy efforts a little easier.