Pain. It is the No. 1 reason people with bleeding disorders consider total knee replacement surgery.

“I was in a lot of pain. It was constant,” says Tom Powell, 52, a retired computer industry manager in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Bleeds from his severe hemophilia A had affected both knees. Business travel often meant sitting for long periods on a plane. “My knees were in such bad shape that they were stuck in a 90-degree position or straight out. On more than one flight, I was the last one off,” he says.

Powell was knee-deep in knee pain. “I couldn’t ride a bike. Walking long distances was out of the question. Even everyday life activities—like getting up from the dinner table—were hard to do,” he recalls. His hemophilia treatment center (HTC) team at the University of Colorado had documented his worsening condition. They suggested total knee replacement surgery (also called total knee arthroplasty).

For many, the knee is the target joint that causes the most problems and pain. Repeated bleeds contribute to arthritis and loss of motion, which can impair daily activities, work and quality of life. The decision to have a total knee replacement operation should be made with your HTC team. Successful surgery has much to do with you, the patient. The more willing you are to persevere through the lengthy physical therapy, say healthcare providers, the better the results.

The Knee Joint

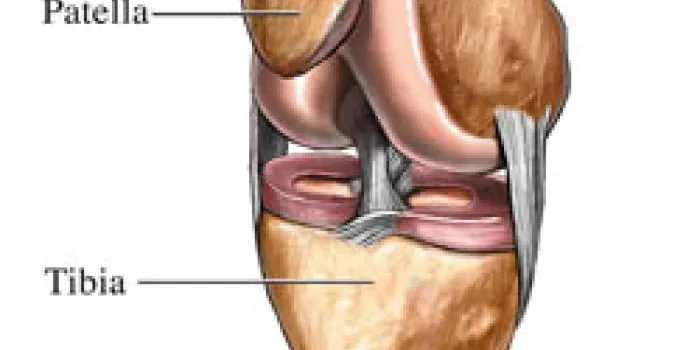

The knee is a hinge joint composed of the femur, the long bone of the thigh; the tibia, or shin bone; and the patella, the kneecap. It performs two basic motions: flexion, or bending, and extension, or straightening. It is also capable of a small degree of rotation. Surrounding ligaments hold the joint together and stabilize it, while muscles help it move effectively.

Normal range of motion (ROM) for the knee is 0 to 140 degrees of flexion and 0 degrees for full extension. A loss of 2 to 5 degrees of flexion is manageable, but a 7- to 10-degree loss can cause limping or trouble negotiating stairs.

Knee bleeds can be destructive. Damage is done when recurrent bleeds cause the synovial membrane, the protective lining around the joint, to become inflamed and thicken, making it more prone to bleeding and swelling. The iron in blood can destroy the membrane, erode the shock-absorbing cartilage in the joint and result in arthritis. All of these impinge on the joint, preventing it from moving smoothly. In severe cases, the knee can become deformed, causing a patient to become either bow-legged or knock-kneed, or assume a permanently flexed position, called a flexion contracture.

Surgery Candidates

“Candidates for knee replacement surgery are those in whom the knee joint has advanced to a stage where the arthritis that’s present is severe,” says Jerome D. Wiedel, MD, orthopedic surgeon at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Aurora. As a result, they have reduced function in one or both knees. When the symptoms are not controllable via conservative measures, such as therapy and the use of anti-inflammatory medications, surgery may be the solution, he says. If synovitis is present, a synovectomy is performed to remove the damaged synovial lining.

Wear and tear in the knee can occur earlier in this community than in the general population. “It’s not unusual to see patients face this decision when they’re in their late 20s and 30s,” says Wiedel. These patients grew up after prophylaxis was available, did not have access to it because they lived in another country or had an inhibitor. Whereas knee replacements in the general population are generally performed in people older than 55, in this community they are done much earlier. Most are done in men ranging in age from 35 to 50 years old, but some patients are in their late teens and some are as old as 70.

For patients with two bum knees, the dilemma is whether to do both at once or one at a time. “For a bilateral knee replacement to be appropriate, both knees are at a stage where they need to be done and one isn’t worse than the other,” says James V. Luck, Jr., MD, chief of orthopedics at the HTC at the Los Angeles Orthopaedic Medical Center. He is also president, CEO and medical director of Orthopaedic Hospital. The doctors’ dilemma is the degree of range of motion loss vs. what surgery can gain. If range of motion is still good, despite arthritis, Luck says the outcome can be encouraging. “On the other hand, if the patient has lost a lot of motion, the result may be that by doing them both at the same time, you don’t end up with decent range of motion in either one.”

After Powell realized that separate surgeries and the physical therapy would take nearly two years of his life, he made up his mind. “I asked Dr. Wiedel, ‘How about if we do both at once?’ He told me it would be a little tougher and would take more effort on my part. In 1993, I did the manly thing—I had both done at once.”

That decision should be made with the peace of mind that comes from having a knowledgeable, experienced healthcare team. “It’s critical that these surgeries be done at an HTC, where the hematology group works as a team, including the hematologist, surgeon, nurse and physical therapist,” Wiedel stresses.

Reasonable Expectations

“In general, the motion the person will get back depends on the motion they started with,” says Wiedel. The patient with advanced arthritis and limited ROM will gain less than one who goes into the surgery in better shape.

Powell admits he had high hopes. “My expectations were that I was going to get two good-as-new knees, or better than new, not two knees that would work well.” The replacement hardware cannot withstand impact and shock. For active men, that means no more pounding the pavement. “My PT [physical therapist] made it clear that I should not take up skiing or running marathons,” says Powell. Most racquet sports and basketball are also off-limits.

Still, the surgery should help patients move more fluidly. “The prosthesis gives them motion that is more functional, more conducive to normal daily walking and activities,” Wiedel says.

Artificial Knee Components

Metal and plastic components replace the defective knee parts. The femoral component is made of cobalt-chrome or titanium. “It resurfaces the bone with an artificial shape that is the natural shape and replaces the cartilage that has been lost,” Wiedel says. The tibial component has a metal base plate that fits on top of the shin bone. An insert made of polyethylene fits onto the base plate between the femoral and tibial components, providing the hinging motion of the knee. “The patella has a plastic cap placed on its undersurface so it tracks over the front of the joint in the natural way,” says Wiedel. Cement is used to affix the parts to surrounding bone.

Potential Problems

All surgeries carry a potential risk of complications. In 2005, Luck, along with co-author Mauricio Silva, MD, published the results of one of the first long-term studies of knee replacements in people with hemophilia in The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. The study of 90 knee surgeries in 68 patients during a 26-year period revealed that the late infection rate, from six months to 17 years after surgery, was high—16% vs. 1% to 2% in the general population. This figure is consistent with that found in other studies. In patients who underwent bilateral knee surgery, the rate of infection was 22%.

“The reason for the increased incidence of late infection is self-infusion,” not the surgery itself, says Luck. “If patients are not meticulous about their technique, they get bacteria in the blood stream that go to the knee.” At the first sign of infection, they need to contact their physician, he urges.

A further finding was the refutation of the hypothesis that patients who were HIV-positive were more susceptible to infection. In the study, which compared patients with similar CD 4 counts (a measure of the immune system’s ability to fight infection), the differences were negligible. Infection developed in 17% of patients who were HIV-positive, compared with 13% of those who were HIV-negative. “We have shown clearly that although there is an increased incidence of late infection in patients with hemophilia, it is not related to HIV status,” Luck avers.

Sepsis, a systemic infection of the blood, can occur in patients with inhibitors who have the knee surgery. Historically, bacterial infections have come from airborne spores in the operating room. Now, the cause is usually a central venous access device. “Systemic blood poisoning is most common in patients with some type of venous access line, especially one that is external,” Luck says.

The study also revealed the need for preprocedural antibiotics. “The use of prophylactic antibiotics before dental work or any other invasive procedure was another important finding,” says Luck.

The body’s reaction to surgery is to create scar tissue on the skin and in the joint, a condition called arthrofibrosis, or stiff knee syndrome. The surrounding ligaments and tendon stiffen, tightening the knee joint capsule, restricting the natural motion between the femur and the tibia. If ROM exercises are not done soon after surgery, some patients can permanently lose full flexion or extension.

As with any replacement surgery, the artificial knee parts can loosen and even fail. The artificial components wear out with age, which Wiedel says is inevitable. Infection, which can cause failure of the prosthesis, results in its removal. However, the rates are still relatively low. “Now that we have better replacement therapies and understand the need for aggressive use of factor replacement, loosening and mechanical problems aren’t any higher than in the general population,” Wiedel says.

[Steps for Living: Treatment Basics]

With the advent of better replacement parts, the need for revision is now measured in decades, not years. “In individuals who don’t abuse the joint by overstressing it, the replacement will last 20+ years and theoretically could go 30+ years,” says Wiedel.

Prepping for Surgery

“At our center, we have patients learn all the exercises preoperatively to gain as much strength in the quadriceps and hamstrings as possible beforehand,” says Sharon Funk, PT, University of Colorado Denver Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center. “The more you can do upfront, the easier the rehab is afterward.” The HTC nurse, PT and social worker also discuss the procedure, encouraging patients to share any fears or concerns. “We tell them, ‘It’s going to hurt. You are going to have to work hard, but each day it will get a little bit easier.’”

Patients typically stay in the hospital for two weeks. Pain medications and antibiotics are given as long as they are needed. The hematology team determines whether the factor infusions are continuous and how long to sustain them after surgery. But patients are not resting in bed for long. Continuous passive motion machines keep their legs moving to promote blood circulation and prevent clot formation and swelling. Most physical therapy begins early and is aggressive.

Partners in Physical Therapy: A Tale of Two Patients

Larry Hammerness, 45, had a troublesome right knee that required a synovectomy when he was 10 years old. “It had created so much scar tissue that even moving caused bleeding,” he says. Later, he self-infused for episodic bleeds caused by his severe hemophilia A. Always active—he surfs, skis, swims and cycles—the Los Angeles photographer underwent knee replacement surgery in 2002 to relieve chronic pain.

[Steps for Living: The Pain Facts]

Previous surgeries to repair a broken hip and to fuse an ankle led Hammerness to believe he was ready for rehab. He remembers the rigorous twice-a-day sessions the first few weeks, falling asleep at home, exhausted afterward. “You have to be really committed to the physical therapy,” he says. “I probably did 80% of the work. In retrospect, I wish I had done the other 20%.” The result: Hammerness has lost flexion in his right knee; he can bend it only to a 90-degree angle.

For physical therapy after knee surgery, the truism holds: What you put in, you get back. “The goal of the physical therapy is to get full extension, passively and actively, and to regain flexion,” Funk says. “I’ve seen as much as 130 to 140 degrees, but most people do not get that much.” She says patients are usually not discharged from the hospital until they have at least 90 degrees flexion. “They are expected to work at home and in outpatient PT to regain more. If you don’t achieve a good outcome and your preoperative severity of joint and muscle restriction is not severe, perhaps it’s because you didn’t work long or hard enough on your physical therapy.”

Funk begins PT the day after surgery. Patients try to stand, take steps using a walker and put minimal weight on the joint. Sometimes weight bearing may be restricted by the surgeon, based on the type of prosthesis used. “There’s going to be pain when they walk, when they contract the quadriceps muscle and when they bend the knee. But the pain is different from the constant arthritic pain they’ve lived with for so long,” Funk says. Unlike arthritis pain, the post-op pain diminishes slightly each day; eventually it subsides.

Back in bed, patients work on leg lifts to strengthen the quad muscle and heel slides to bend the knee. “Each day, we do more of each of these: walking longer distances, continuing to work the quadriceps muscle correctly, getting full extension and regaining flexion.”

Therapy is timed with factor infusions to minimize bleeding and with pain medications to maximize comfort, Funk says. Patients progress rapidly from a walker to crutches, easing into weight bearing as tolerated. “You have to have a quad that’s strong enough to support full weight. That may take a month or more,” she says.

The amount of physical therapy is physician-specific and hospital-specific, says Funk. “Twelve weeks of therapy is minimal. It could go on for months, or a year.” The best results are achieved by patients who follow through at home. “If you get off to a good start, you can work on it independently if you’re driven enough,” she says.

“Driven” describes Powell’s mindset about rehabbing his knees. “I was aggressive about the PT,” he says. “I knew I was in for a lot of it. If I didn’t do it, the surgery would all have been for naught.”

The therapy sessions conducted at his home for six months were difficult, Powell confesses. “The exercises hurt. While the PT was bending my leg over and over, I played lots of mind therapy games rather than taking prescription drugs for the pain.” Picturing himself on a beach in Hawaii helped distract him. At one point, Powell pushed a little too hard. “I didn’t feel that my left knee had as much range of motion as it should. The PT said, ‘If I apply more pressure, I’ll snap it in half.’”

All of Powell’s hard work paid off after the surgery. He has achieved two goals: resuming hiking and biking in the mountains with his family. “I wanted to be able to keep up with my wife and two girls. I didn’t want to be left in the dust.” With his new knees, he hiked the scenic trails at a nearby state park, climbing to an elevation of 10,000 feet.

Biking was a bit more challenging, so Powell customized his cycle. “I bought an electric-assisted bike and modified it so the pedals would fit the amount of revolution I could do.” That allowed him to ride through the 16-mile Glenwood Canyon trail, along the banks of the Colorado River, between sheer cliff walls. “I could zip up and down the steep elevations. I got to the point where I could go 20 miles before the battery went dead,” Powell says with pride.

“We’ve had excellent results overall at our center with the procedure,” says Funk. “We have high expectations for good motion, strength and quality of life afterward.”

If you’re contemplating knee replacement surgery, heed the advice of two patients who have been through it. “Don’t put it off until you virtually can’t walk,” says Powell. “Make sure you have the commitment and do all the PT.”

“It’s the last time I had to deal with pain in my knee. It’s totally worth it,” adds Hammerness.