“Oil can.” The Tin Man’s request in the movie The Wizard of Oz offers a simple solution for his rusted joints. If only a squirt of oil could offer such a quick fix for people with bleeding disorders whose elbows are the sites of repeat bleeds and advanced arthritis.

Kent Greer, who lives in Fruita, Colorado, and has severe hemophilia A, started having elbow bleeds as a child. “Unfortunately, I was one of those kids who didn’t get the factor VIII or the concentrate real early, so I wore braces on both elbows and both legs starting when I was about 14.”

As Greer got older, his elbows became target joints for bleeds. “Chronic pain was my primary problem,” says Greer, 53, a retired hospitality industry worker. On a scale of one to 10, the pain could skyrocket to eight or nine, he says. Occasionally, he had pain at rest. Loss of range of motion also began to occur. Greer estimates that his elbows were flexed in a 45-degree to 70-degree angle. “Both radial heads were very deformed, with very limited motion in both my elbows.” In 2004, Greer had radial head excision surgery on his left elbow; a year later, he had the right one done.

[Steps for Living: The Pain Facts]

These days, with the advantages of early diagnosis and prophylaxis regimens, fewer men will have to face elbow surgery. (See the National Hemophilia Foundation’s Medical and Scientific Advisory Council’s [MASAC] Recommendation #102, stressing the need for more data collection on joint health, and MASAC Recommendation #179 on prophylaxis therapy.) Still, after the knee, the elbow is one of the most commonly affected target joints for recurrent bleeds. It is important to understand what happens in the elbow when there is a bleed. A vicious cycle of bleeding and tissue degradation in the joint can contribute to loss of function and pain over time, setting up a scenario for surgery.

Gist of the Joint

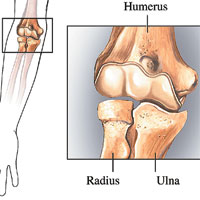

The elbow bones create a hinged joint where the humerus of the upper arm connects with the radius and ulna of the lower arm. The joint makes four main types of movements: extension (straightening), flexion (bending), pronation (rotating the forearm from palm up to palm down) and supination (rotating the forearm from palm down to palm up).

Cartilage protects the surfaces of all three bones in the elbow, but is easily damaged when bleeds occur. Since blood is not normally found in joints, it can be downright destructive. It does its damage both indirectly and directly: Blood produces inflammation of the synovial membrane, which lines the joint and secretes fluid to keep it lubricated, causing it to release enzymes that destroy the cartilage. In addition, the iron component in blood directly damages the cartilage.

The synovium is not equipped to eradicate large amounts of blood. One bleed is manageable, but multiple bleeds are not. “Once you have several bleeding episodes, that synovial membrane becomes very thick and can’t take out that amount of blood that is inside the joint,” says Mauricio Silva, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at Orthopaedic Hospital in Los Angeles. “Over time, the cartilage becomes very thin. Layers of cartilage can completely wear off, leaving bone exposed.” Bone-on-bone contact can create pain for the patient.

The synovium is not equipped to eradicate large amounts of blood. One bleed is manageable, but multiple bleeds are not. “Once you have several bleeding episodes, that synovial membrane becomes very thick and can’t take out that amount of blood that is inside the joint,” says Mauricio Silva, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at Orthopaedic Hospital in Los Angeles. “Over time, the cartilage becomes very thin. Layers of cartilage can completely wear off, leaving bone exposed.” Bone-on-bone contact can create pain for the patient.

In addition, the radial head can become enlarged and misshapen. “Instead of being a very round structure, it’s irregular,” says Silva. “That probably doesn’t happen in any other entity than hemophilia.” Silva surmises that elbow bleeds in children and teens stimulate the growth plates around the radial head, increasing its size. When the forearm is rotated, the oversized head of the radius can pinch the synovium between the radius and the ulna, leading to more pain.

Preventive Measures

When it comes to elbow bleeds, early prevention through regular prophylaxis is the best option. Once a bleed has occurred, aggressive intervention is important. “Sometimes we can manage it with prophylactic factor treatment alone,” Silva says. Braces or splints can immobilize an elbow after a particularly bad bleed, but have limited, short-term value.

If factor treatment alone does not reduce the frequency of elbow bleeds, a synovectomy (a procedure to remove the inflamed and damaged synovial lining) may be recommended. “Most of the time, synovectomies are effective and can decrease the frequency of bleeding,” says Silva. “If done early enough in a child or young teen, the patient might be able to outgrow the damage that occurs as a result of chronic bleeds.” (See “Treating Joint Damage with Synovectomy,” HemAware, November/December 2006, p. 52.)

Prior to Greer’s elbow surgeries, radiosynovectomies were performed. “They injected both my elbows with radioactive isotopes, and it cut down on the bleeds,” he says.

Surgical Options

Elbow surgery is usually only considered after all other options have been exhausted. Total joint replacement surgeries, or arthroplasties, have become more standard in the bleeding disorders community. It’s not uncommon to meet men with knee and/or hip replacements. Even so-called routine replacement surgeries, though, carry risks of infection, complications and loosening of the prosthesis itself.

“With total knee replacement, there is a risk of infection of about 16% in people with hemophilia, compared to only 1% in nonhemophilic patients. That creates an even greater risk for elbow replacement,” says Silva. The risk for infection at the elbow is elevated because of the lack of large muscles to cover the prosthesis. “The metal is almost exposed underneath the skin,” he says.

Currently, elbow replacement surgery for people with hemophilia is somewhat controversial. “We don’t do total elbow replacements,” says Silva of the team of orthopedic surgeons at Orthopaedic Hospital in Los Angeles. His mentor did a few such surgeries in the 1970s, but stopped after patients experienced infections. Silva cites studies conducted at Oxford in England (published in 2003) and at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota (published in 2004) that demonstrated other risks, as well. When combined, the researchers looked at the efficacy of elbow replacement surgeries in 12 patients with hemophilia. “About six of them had major complications, including infections—that’s a main concern,” says Silva. “One had a vein thrombosis and another had a nerve injury. At this time, that procedure is not our choice.”

The surgery Silva does choose, however, is radial head excision. It effectively removes the mechanical blockage created by the oversized radius. To rotate your elbow, the radial head has to join an articular surface on the ulna. “Because this radial head is so enlarged and irregular, every time you try to rotate, that irregularity is stopped by the proximal ulnar facet,” says Silva. “Once you remove the radial head surgically, you have removed the mechanical blockage and the patient can return to rotation.”

The surgery Silva does choose, however, is radial head excision. It effectively removes the mechanical blockage created by the oversized radius. To rotate your elbow, the radial head has to join an articular surface on the ulna. “Because this radial head is so enlarged and irregular, every time you try to rotate, that irregularity is stopped by the proximal ulnar facet,” says Silva. “Once you remove the radial head surgically, you have removed the mechanical blockage and the patient can return to rotation.”

Radial head excision surgery is often accompanied by a synovectomy. “They are usually done together,” says Silva. “One you take the radial head out, if you find a very thickened synovium, it’s a golden opportunity to take it out.”

A 2007 research study co-authored by Silva and James V. Luck Jr., MD, published in The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, reviewed 40 radial head excisions performed in men with severe hemophilia A or B during a 35-year period, from 1969 to 2004. Patients referred for surgery had severe pain, limited range of motion and chronic bleeding in their elbows. The results showed that the surgery successfully reduced pain in 70% of patients; of those, 30% reported complete pain relief. Further, bleeding frequency was decreased and there was a low rate of complications. One patient developed nerve palsy after the surgery, but it resolved within six months. In addition, there was a mean gain of 63 degrees in the pronation/supination arc in the forearm, which Silva calls “a significant improvement.”

Preferred Patients

When pain and immobility interfere with daily living, people are ready to consider radial head excision surgery. “Anything I enjoyed doing was limited,” says Greer. “When you have that much limit to your joints, it pretty well curtails your activities. I had about 20 degrees of motion in my left elbow when I had the surgery done.”

While there is no typical patient, there are populations of patients for whom surgery is the best option. “Generally, the patients I see at my center are between their mid-20s and early 50s,” says Sue Geraghty, RN, MBA, of the Mountain States Regional Hemophilia and Thrombophilia Center in Aurora, Colorado. “The degree of debilitation they have is dependent on the frequency of bleeding into the joint.” Someone who develops a target joint as a child and has an average of four to eight bleeds into the elbow by the time he is in his 20s will have much more degeneration, she says, than one who has his first elbow bleed in his teens.

Many people with limited movement in their elbow find ways to manage. “What we see a lot of times [is that] they’ve learned to compensate,” says Geraghty. “If you watch, they’re opening [the door] with their whole body, leaning over to get their hand to open the door, as opposed to the motion coming from the elbow.”

The yardsticks Silva uses to determine the need for elbow surgery in people with hemophilia are: pain, radial head enlargement, and limitations in pronation and supination in the forearm. “If you cannot rotate your forearm, it’s very difficult to perform personal hygiene or feed yourself,” he says. “If we can improve it with surgery, that is a very important gain in your quality of life.”

On the other hand, not all patients with limited movement in the elbow and arm are candidates for surgery. “If I have a patient who has a bad elbow—it looks terrible on the X-rays, the joint is bad, the radial head is bad—but there is no limitation for pronation/supination, I will be a little reluctant to excise the radial head because the patient will not gain much from the surgery,” Silva says. People who want to improve flexion and extension are told the same thing. “This procedure is not going to improve that,” Silva says. “Patients need to understand that so the goals are clear.” The research he conducted with Luck showed that after surgery, only two degrees of flexion, at best, were gained in the elbow.

On the other hand, not all patients with limited movement in the elbow and arm are candidates for surgery. “If I have a patient who has a bad elbow—it looks terrible on the X-rays, the joint is bad, the radial head is bad—but there is no limitation for pronation/supination, I will be a little reluctant to excise the radial head because the patient will not gain much from the surgery,” Silva says. People who want to improve flexion and extension are told the same thing. “This procedure is not going to improve that,” Silva says. “Patients need to understand that so the goals are clear.” The research he conducted with Luck showed that after surgery, only two degrees of flexion, at best, were gained in the elbow.

Also, Silva will not perform elbow surgery on children under the age of 15 because they are still growing. “I will not do it on a patient with an open physis [growth plate],” he says emphatically. “The proximal aspect of the radius can regrow and can become a problem again. The total length of the radius can be altered and can actually change the distal radial-ulnar joint.” Surgery performed on a child who is not done growing could lead to uneven arm lengths down the road.

Pre-op Workup and Post-op Workout

Candidates for radial head excision need to have a workup prior to the surgery. That includes a full musculoskeletal evaluation, measuring the degrees of flexion and extension, pronation and supination, and strength testing. Depending on the surgeon, radiological evaluations usually include X-rays and an MRI.

Taking a bleeding history is also important. “We ask them such things as the age at first bleed into the elbow joint, frequency of bleeding in the past, current frequency of bleeding and whether they are on an anti-inflammatory medication,” says Geraghty. “These help us determine whether someone has significant arthritic changes versus whether they are still bleeding into the joint.” The combined information provides the surgeon with the most accurate picture of the state of the elbow before surgery.

Silva says the surgery is relatively simple. “We approach the elbow through the lateral side, spread the muscles apart and open the capsule.” That provides the ideal position to expose the radial head, which is then removed through a cut just below the radial head (neck).

Patients with hemophilia typically stay in the hospital a week to 10 days, says Silva, mostly to make sure bleeding is under control. “The arm is in a splint in full supination after surgery, because that’s the motion we want to recover,” he says. “By day three or four, we take the splint down and start physical therapy.”

Physical therapy helps restore range of motion, strengthen weak muscles and prevent repeat bleeds into the joint. “After surgery, we’re looking at regaining range of motion—that’s the first step,” says Pattye Tobase, PT, DPT, OCS, University of California San Francisco Hemophilia Program. “Any time there’s an invasive procedure, you can have scar tissue buildup. If the surgery has gone well, we try to get them moving quickly—within the first week post-op.”

Once the elbow is moving well again, strengthening exercises are added. “We start them with gentle isometrics, meaning they’re contracting the muscle without moving the joint,” says Tobase. Patients control the degree of contraction, she says, starting at 25% and building up to 100%. Moving the joint has an added bonus—it helps decrease the swelling, moving built-up fluids out of it.

Next, Tobase encourages patients to progress to resistance work. “They can start with resistance bands or light weights, about one pound,” she says. The reason for not taxing the elbow, she says, is that compared with the leg, for instance, it has fewer, smaller muscles. Elbow surgery places a lot of trauma on a relatively small joint. (For more on resistance bands, see "Exercising Inexpensively," HemAware Spring 2010.)

The physical therapy regimen begins in the hospital but must be maintained at home. “The surgery can be successful, but how it turns out a year from now really depends on what that person does at home,” says Tobase. Depending on the patient, the therapy can take several months. She is very clear with her patients, telling them up front, “This is what we expect from you to make this a successful surgery. That means doing something every day—moving the joint in some way.”

Your hemophilia treatment center (HTC) should be your first stop on the road to surgery. “The best advice I can give is to always go to your HTC,” says Silva. “They have hematologists and orthopedic surgeons who are accustomed to treating patients with this problem.” But be aware that most orthopedic surgeons specialize in either adult or pediatric patients, not both. “Families need to recognize that there may not be a surgeon in their area who can provide the service they need,” says Geraghty. “Talk with your HTC about where to go for referral to get the best surgical option.”

Activities Again

Greer, the retired hospitality worker in Colorado, assesses the value of his elbow surgeries by the activities he’s been able to resume. “I’ve regained quite a few things—indoor activities, such as housework and shooting pool, and outdoor activities, like fishing and shooting my revolvers. Those were very limited before I had the surgeries.”

He estimates he’s gained 15 to 20 degrees of motion in his elbows, but cannot straighten them completely. Greer takes it all in stride, though. “I still have some joint pain in my elbows, but it’s lessened considerably. I still have an occasional bleed, but that’s something those of us with hemophilia have to live with.”

Although he says the surgeries were expensive, Greer doesn’t hesitate to recommend them to others. “It is expensive, but so is factor VIII. It gave me a lot more freedom and brightened my outlook on life. You can’t put a monetary value on being able to do things again.”